THE BATTLE FOR TINIAN

FOR GENERAL BACKGROUND FOR TINIAN BATTLE SEE FOOTNOTE 1 BELOW

The air, sea and land battle for Saipan put America in the Catbird Seat for the rest of its Pacific Ocean War with Japan. With the linchpin to Japan's outer ring of inner defenses in the Central Pacific in America's hands, Saipan cut off Japan's lines of transit into the Central and South Pacific. From there, it was a short hop across a narrow channel to Tinian. This brought Japan's home islands within range of US strategic bombers.

Japan's fighter pilot Saburo Sakai said it best:

"The Americans had invaded Saipan. In more ways than one the war had come home. Saipan was not very distant. The maps were unrolled and our people looked for the tiny dot that lay not far from our coastline then looked at each other. They began to question, never aloud, but in furtive conversations, the ceaseless reports of victories. How could we have smashed enemy ships, destroyed his planes, decimated his armies, if Saipan had been invaded?

It was a question which everyone asked, but very few dared to answer. No sooner did we receive the news of the Saipan attack than powerful units of our fleet sailed for the Marianas to engage what everyone at Yokosuka knew would be one of the decisive battles of the war. We were no longer invading foreign islands, we were guarding the very portals of our homeland. The next morning (our) Yokosuka (air) wing received orders to transfer to the island of Iwo Jima." Samurai! by Saburo Sakai, with Martin Caidin and Fred Saito, by Naval Institute Press 1957

Surprise U.S. carrier air strikes pummelled the Marianas starting June 12, 1944. Convinced that U.S. amphibious forces were steaming east to invade its key island strongholds, Japan's Imperial Mobil fleet, nearly all its seaborne carrier fleet, and nearby land garrison air forces, sallied forth from the Philippines. US task Force 58 sent two carrier task groups north to intercept aircraft reinforcements from Japan, then regrouped and sailed west into the Philippine Sea to engage Japan in the largest seaborne air battle in history.

Launched from some 24 aircraft carriers, 1,350 carrier aircraft and 300 land based aircraft clashed on June 19 and June 20 over the Philippine Sea. 123 US planes were splashed, killing 109 airmen. 550 to 645 Japanese planes pitched into the Pacific, killing 2097 airmen. Japan's offensive seaborne air power died in the Central Pacific, never to recover. US ground forces now were free to rip the island heart out of Japan's outer ring of inner defenses at Saipan, Tinian, and Guam. America's Fleet - its blue water gunships, its sea-borne air forces and amphibious armies, and its massive logistics train, now had unfettered freedom of maneuver and resupply across the vast ocean spaces from Hawaii to the South Pacific up to Dutch New Guinea and across the Central Pacific to the Marianas, putting American airpower on the doorstep of Japan's home islands.

Thus the US amphibious landing on Saipan kick started a chain of events that blew open the door for America to seize from Japan overwhelming power in the Central Pacific, and from there to move east, south and north at will, going up along the inner rim of barrier islands to the Asian Mainland proper, targeting islands of choice, and combinations thereof, including Pelieu, the Philippines, Formosa, Okinawa and islands north to Southern Japan. After Saipan fell to the Americans, their challenge was not how to win the war, but how to best end the war with victory.

-----

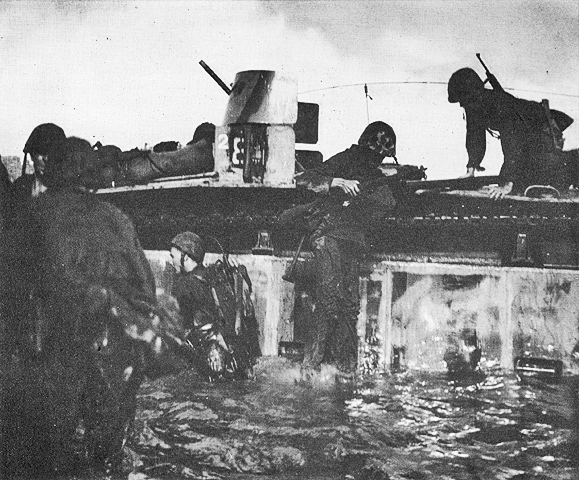

But immediately after Saipan was declared secure, the choice was obvious. To solidify and expand that power, the 4th and 2nd Marine Divisions left Saipan on on 24 July, crossed a three mile ocean channel, rounded the north end of Tinian, and seized by force the platform from which America would end the Pacific Ocean War one year later. The 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion led the first waves of that Tinian assault, onto its narrow White Beaches.

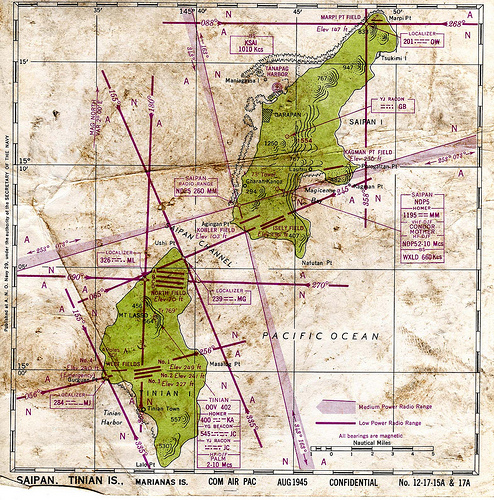

Tinian, 5 miles wide at most, is 12.3 miles long. Coral cliffs rim its shoreline that is otherwise impervious to amphibious assault but for three landing sites, two up north, one down south, tucked into opposite sides of the island . Tinian's major defenses clustered around these landing sites and nearby airfields. Ushi airfield and its nearby artillery on Tinian's north end posed the Tinian's greatest threat to US landings on Saipan's beaches only a three miles away across a narrow sea channel. So one of America's first tasks in its seizure of Saipan was to neutralize Ushi Airfield and enemy artillery on Tinian's north end.

BACKGROUND PERSPECTIVE IN A NUTSHELL:

When America entered World War 11 on Dec. 7. 1944, Japan had already been at war since 1931 with China then also the Soviet Union during which time the Japanese Imperial Army took the lead with Japan's Navy in support. Germany's 1940 conquest of the Netherlands and France and it's war against Britain opened up the practical possibiltiy of Japan's occupanion of French Indo China and its seizure of resource rich British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. Germany's summer of 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union opened up the practical possibility of Japan's reconquest of Soviet Manchuria, and seizing additional Soviet lands to the east and north of Manchuria. That same summer America embargoed oil and rubber trade with Japan, jumpstarting Japan's invasion of territories controlled by the Western Colonial powers, French Indo-China, British Malaya (including Singapore), and the Dutch East Indies. Japan's thrust across the Celebese Sea altered Japan's strategic war plans. Mahan's decisive naval battle with America now most likely moved south along the line of the Marianas (Saipan and Tinian), the Western and Eastern Carolines, and Palau, a line defensively anchored by a bastion at Truk atoll, and guarded by a reconnaissance line as far east as the Marshall islands. The advent of America's revolutionary long range heavy B-17 bomber caused Japan to reconsider Truk's southern flank defenses, extending them 1400 miles southeast to Rabaul on New Britain in the Bismark Archipelago at the northwest edges of the South Pacific.

Insert more here.

Tinian then was still under the command of a highly experienced air combat leader. Vice Admiral Kakuji Kakatu earlier commanded Carrier Division 4 in the December 1941 air attacks that supported Japan's invasion of Douglas MacArthu's r's Philippines. He next directed Fleet air operations against the Dutch in the East Indies and British Naval forces defending India and Ceylon. In June 1942 he directed the carrier air task force (Ryūjō and Jun'yō) raid against Dutch Harbor in US Aleutian Islands, part of Battle of Midway then 2nd Carrier force air operations Solomon Islands Campaign until on July 1, 1943 he took command of the First Air Fleet headquartered on Tinian tasked with land based air defence of Japan's "unsinkable island aircraft carriers" in the Central Pacific and lines of transit through those vast ocean spaces to key strongholds within Japan's southern Empire.

(Insert Material here for editing --- Ultimate force of 1600 planes. Vice Admiral Kakatu the 1st Air Fleet CO was building 16 air bases throughout the Marianas on Tinian, Saipan, Guam, Pagan and Rota for 600 warplanes. 400 planes were operational when the US Navy struck Admiral Kakatu in his HQ at USHI AIRFIELD on 11 June. By 20 June the US Fifth Fleet had destroyed most of Admiral Kakatu's warplanes, nearly all 400 (incl. many of 107 planes destroyed at Ushi on 11 June) along with hundreds of carrier based aircraft and 3 fleet carriers at the Battle of the Philipinne sea)

STRATEGY, PLANNING, AND PREPARATION FOR AMPHIBIOUS LANDINGS ON TINIAN:

PHASE 1 OF TINIAN CAMPAIGN: EDITING in PROGRESS BELOW as of DEC. 19

Accordingly, Admiral Spruance's 5th Fleet Directive, issued to Task Force 58 well before the Saipan landing, stated:

"Destroy enemy aircraft and aircraft operating facilities, and antiaircraft batteries interfering with air operations; Destroy enemy coast defense and antiaircraft batteries on SAIPAN and TINIAN; Burn cane fields in SAIPAN and TINIAN which may (conceal) enemy troops; Employ aircraft to destroy enemy defenses at SAIPAN, TINIAN... ; Employ battleships and destroyers to destroy enemy defenses at SAIPAN and TINIAN."

Thus, Tinian's conquest is best understood as a two-phase campaign beginning with hostilities that opened the campaign to seize Saipan.

The first objective here was to gain control of the skies over, and seas around, the islands of Tinian and Saipan, isolating both from outside aide and reinforcement. And then to neutralize, degrade, and ultimately eliminate the threat that Tinian posed to US amphibious assaults and follow on US ground operations on Saipan. Thus Admiral Mitscher's Task Force 58's Fast Carrier air strikes first hit Tinian's airfields for three days starting on 11 June. Next its fast Battleships targeted northern Tinian's long range guns and artillery on 13 June. These combined air sea operations established close in US air and sea dominance around and over the islands before 15 June when the Marines landed on Saipan's western beaches, although intermittent and lethal, but declining, enemy air activity into and out of Northern Tinian, and Japanese shelling of Saipan from Northern Tinian, would continue thoughout the Saipan Campaign, as did US continuous US counter battery fire into Northern Tinian in an effort to neutralize and eliminate those threats. Nevertheless Admiral Spruance judged that he could prudently leave behind the US Alligator Fleet (Task Force 52) to temporarily fill the void otherwise created when the main body of his blue water 5th Fleet left Saipan 3 days later to engage Japan's Fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. To fill that void he positioned Task Force 52 for two critical tasks, namely, a rear guard blocking action if needed to maintain local air/sea dominance around Saipan and Tinian, and otherwise solely relied on the Alligator Fleet's lesser guns and air power to support the Marines fierce fight on Saipan. The results were monumental. During this 3 day interim period the US Navy destroyed Japanese sea and air power in the Central Pacific while the Marines firmly secured their beachhead on Saipan, Japan's key stronghold in the Central Pacfic.

Thus The Saipan/Tinian operation, very early on, demonstrated the interactive advantages that sea/air dominance can bestow on Amphibious Assault while the resultant threat and success of Amphibious Operations on Saipan first enabled and then mutually supported US combined arms operations in a variety of ways, both nearby and at long distance for vast and cumulative advantage. This showed how these otherwise disparate arms, if properly combined, mixed and coordinated can create a myiad of interactive capabilities that mutually reinforce and enable one another for both cumulative and exponential advantage. So here the results were achieved at long or short range, for short or long term advantage, and whether each component acted alone or in tandem as US Commanders mixed these components, and their proportions, in a wide variety of ways to address not only problems, but to create and exploit a myriad of interrelated opportunities. This achieved results not otherwise possible - results that worked on many different levels, and that interacted among themselves and other events, to build a chain reaction that over time generated a series of exponential benefits that radiated throughout the balance of the Pacific Ocean War to its conclusion.

Hence, for example, US land based artillery came into play against Tinian after America secured Saipan's beachheads and nearby airfield (renamed Isely Field) on 20 June. This allowed a US Army Long Tom 155mm artillery battery emplaced on southern Saipan to begin its systematic destruction of artillery and air base facilities on Tinian's north end that still threatened ongoing operations against Saipan. These long range guns also hit anti-aircraft and coastal naval guns as far south as Tinian Town. This in turn also allowed US Army P-47's flying off Isley Field to join US Navy aircraft operating from carriers offshore to conduct reconnaissance missions as well as strafe and bomb Tinian at will up and down the island. Meanwhile, at sea, US Destroyers began to circle the island daily, hitting from all quadrants targets of opportunity, including counter-battery fires and well as road, rail and even air base traffic by day then harassed Tinian Town and road junctions at night. These combined arms operations ramped up quantitatively, and with growing complexity and sophistication, as heavier weapons came into play starting on 24 June.

For example:

On 24 June Battleship COLORADO shelled all three Tinian airfields, and two more US Army 155mm XXIV Corps Long Tom artillery batteries joined the one already shelling Tinian from Saipan. On 27 June the Cruisers INDIANAPOLIS, BIRMINGHAM, and MONTPELIER began a series of special missions. These cruisers used deliberate pinpoint 6/8 inch naval gunfire against fixed targets on Tinian. Now the bombardment not only protected US ground forces fighting on Saipan and US air reconnaissance over Tinian it was also being tailored to degrade and reshape that island's defenses for Jig-Day. Heavy Naval Gunships and Artillery batteries working with US Navy and Army sea and land based strike aircraft focused ever more sharply on coastal defenses, particularly fixed heavy guns as well as logistics, administrative, port, command and control and communications facilities. This included the island's rail and road network (and its motorized transport), what remained of its air bases and forces and AA defenses (incl. their use & resupply). Random chaos reigned. Tinian Town became uninhabitable. But death and destruction could arrive at any spot on the island any time from any direction. Cars, trucks or locomotives using Tinian's roads or rail during daylight hours brought down from the sky overhead their own destruction. This US effort at combined arms, having earlier destroyed Tinian's air force, including its command and control, maintenence and AA defenses, (all Imperial Navy units) now went to work hardest at disarming the balance of the Imperial Navy's 4,110 man garrison. Smashing Tinian's fixed heavy weapons, US Combined Arms thus reeked particular havoc on Tinian's 1400 man 56th Naval Guard Force that manned those weapons and ripped into the 1400 naval construction personnel who maintained those weapons, their revetments, and related base, port and coastal defenses. Thus having earlier ripped up their airplanes, US Combined arms now worked 24/7 to find and rip up whatever was left of Tinian's Naval defense weapons, facilities and personnel. Meanwhile numberous other targets of opportunity (most anything that moved into the open) brought down its own destruction, and the hunt for the origin of mobile artillery fire worked a cat and mouse game, a counter battery fire chased often illusive targets. In doing all of this, US commanders on Saipan compared battlefield results against battlefield objectives and refined their punishments daily, continuously adjusting targets, methods, and mix of munitions and their delivery, to insure follow on destruction as their increasingly wide array of Combined Arms continued to move in tandem around the island day and night.

All of this activity had radically altered the battlefield by 7 July. On that date US Navy spotters reported th at all known fixed Naval Gunfire targets, including coastal and AA gun defenses, on Tinian had been destroyed or rendered inoperable. If true, the following such targets would have been eliminated by 7 July:

1/ At Ushi Point: 3 140mm M3 Naval coastal guns, 3 120mm M10 Naval dual purpose guns, 6 75mm M88 Naval dual purpose (AA) guns, 15 25mm M96 Naval twin dual purpose guns & perhaps 8 13mm anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns;

2/ At White Beach 1: 2 76.2mm M10 Naval Dual Purpose guns, 3/ At White Beach 2 note that 7 25mm M96 Naval dual purpose guns destroyed at Ushi Airfield covered both White Beaches, and that the 3 140mm M3 Naval coastal guns defending the White Beaches from Faibus San Hilo Point had not yet been discovered or yet implace

4/ At Yellow Beach (Asiga Bay): 3 covered 76.2mm M10 Naval Dual Purpose guns, and 4 140mm M3 Naval coastal guns, plus 23 pillboxes including weapons there damaged or distroyed;

5/ At Gurguan Point Airfield: 3 120mm dual purpose Naval guns, and 9 25mm Naval M 96 dual purpose mt guns, plus blockhouse damaged;

6/ At Tinian Town Beaches: 6 25mm M96 Naval dual mt guns. Here note that the 3 120mm dual purpose Naval guns destroyed at Gurguan Point also covered Tinian Town area; and that the 4 120mm M10 dual purpose Naval guns destroyed 3000 yards inland at Marpo Wells threatened US naval ships that shelled Tinian Town's backside from their station off island's SE coast; and that the 3 6 inch British built Naval coast defense guns hidden behind Tinian Town on its south side evaded discovery until inflicting heavy Jig-Day damage on US Naval Forces.

(Elaborate and edit here what follows. ) This assessment relates to Japanese fixed coastal gun and onshore air defenses. It does not include Imperial Army assets in hiding such as the 12 75mm Mt. guns that originally comprised Col. Ogata's 50th Infantry Regiment's Artillery Battalion. Nor what remained of the 6 70mm guns within that Regiment's 3 infantry battalions. Hence it is quite telling that Col. Ogata consolidated those Infantry weapons that did remain on 7 July into a Mobile Counterattack Force that he then initially held in camouflaged positions within Tinian's interior, many equidistant between Asiga Bay and Tinian Town. Exactly when, where, and how, these mobile weapons were later disbursed against the American onslaught is unclear. For, unless they remained hidden and mute, this artillery, particularly if massed, got immediate and fierce US counter battery fire. Although the dates of their destruction is unknown, at least NINE mobile weapons were later found within range of the White Beaches, namely 7 of the 12 75mm Mt. guns and 2 of the 6 70mm pieces. Two more 75mm Mt. gun remnants were found behind Tinian Town's southernmost beach. The rest of Col. Ogata's mobile artillery pieces were not found, or identified and recorded if found. Those that were destroyed during America's bombardment BEFORE Jig-Day help explain the paucity of artillery fire against the White Beach Marines on and after Jig-Day. Those that got into the fight on or after Jig-Day help explain the meager but still lethal camouflaged artillery fire that the Marines encountered after landing on Jig-day.

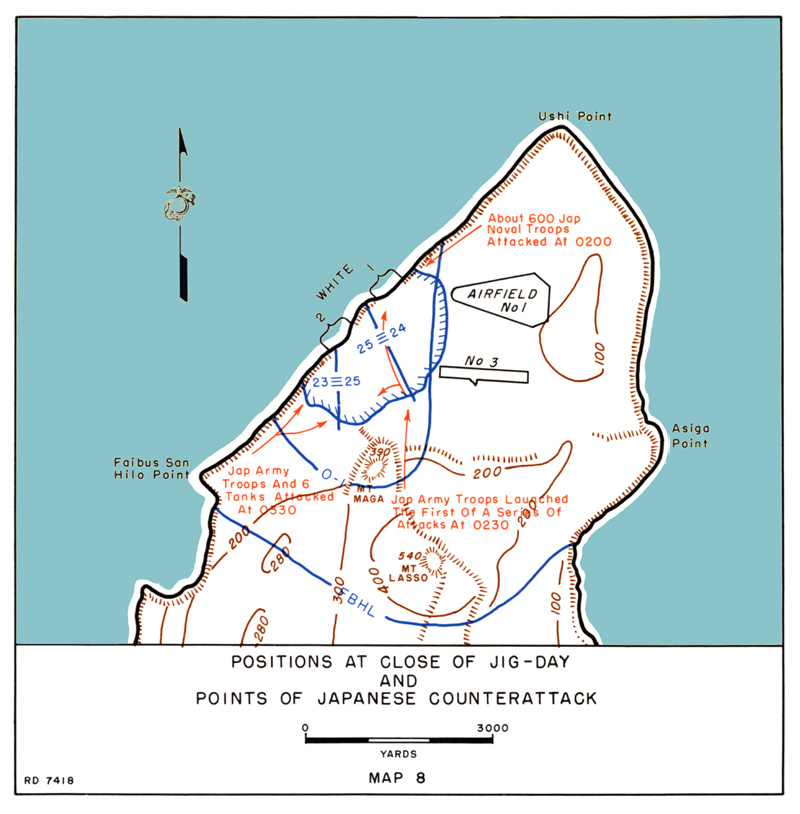

In any case, few (if any) then known Naval Guard Force AA and coastal defense guns survived beyond 7 July. And substantial numbers of the 950 man 56th Naval Guard Force, its anti-aircraft units comprising another 450 men, and its 600 man construction unit, likely perished or were disabled alongside their weapons (including up to 100 machine guns) by 7 July. Tinian's 107 plane 1st Air Fleet had been shattered during the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19-20 June if not destroyed by US carrier air strikes and Naval gunfire before Saipan's 15 June D-Day, and the combat effectiveness of its 1310 men was largely neutered long before Tinian's 24 July Jig-Day by reason of their unit's devastrating defeat, the lose of most all its flyer, planes, and support facitities, including the use of its airbase, and the mental/moral collapse of its Commander who wanted nothing more than to escape the island by submarine. Note, however, that Tinians four infantry battalions likely were largely intact, secure in caves and other camouflaged positions within the island's interior under the fighting spirit of a tough, skilled Infantry Commander. Note also that Tinian's Naval Guard Force had lethal punch left and used it effectively against the Battleship COLORADO and Destroyer NORMAN SCOTT off Tinian Town on Jig-Day morning, and when 600+ Naval personnel carrying weapons stripped off disabled planes at Ushi Airfield attacked the Marines (including 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion) defending the extreme left seaward flank of White Beach 1 before dawn on 25 July, only to be annihilated by those Marines before the sun rose.

((( editing material)

A ----- By now US Combined Arms, operating from land, sea, air, and underwater (submarines) had cut off Tinian's defenders from ALL resupply (save for a dwindling few desperate landings on the remnants of Ushi Air Field and occasional covert small boat mad dash across the Saipan Channel). Now the Tinian's garrison's loss of a weapon, ammo, radio, medicine or other critical tool of combat most often neutered the combat effective of the those who manned them. Whole units collapsed. The airforce first. Airmen took to the hills, to hide. And, as stores of construction materials like concrete ran out, so did critical repairs to critical assets like revetments. Networks of defenses withered away daily, irrevocably.

ALL Of THIS helps to explain why:

ON 7 July Col. Ogata, his naval defense and air forces in tatters, issued a new Plan for the Guidance of Battle that ordered 2/3s of his forces, wherever located, to be prepared to rush to the primary point of U.S. landings, whether on Yellow Beach up north or the Tinian Town Beaches down south, and Col. Ogata ordered his mobile forces to prepare to counter-attack any landing up north across White Beach 2, all upon his later direct orders when issued from his HQ atop Mt. Lasso as the US landing plan unfolded before him. Thus Col. Ogata tried to fill the void left by his Naval coastal and air defense losses by shifting the major burden of Tinian's defense onto what was left of his four army infantry battalions. He designated two of those Infantry Battalions mobile reserves. These would move in tandem with (and be reinforced by) the new Mobile Weapons Battalion that he culled from the remnants of his 50th Infantry Regiment's organic artillery weapons units plus its 42 man anti-tank platoon (with 6 37mm guns) and a 65 man Tank Company with 9 light tanks. One of these mobile infantry battalions (1st Bn. 50th) he positioned just south of his Mt Lasso HQ, ready for its defense. The other mobile battalion (1st Bn. 135th) he placed equidistant from Tinian Town and Mt. Lasso. He located his 3rd mobile battalion, the Mobile Weapons Battalion, equidistant from Yellow Beach and Tinian Town. These three mobile units, on his orders, were to meet any primary beach attack in support of his two fixed battalions. These fixed battalions included his 2nd Bn. 50th Infantry stationed between Mt. Lasso and Ushi Airfield along with what was left of the Naval Guard Force there. His last Infantry Battalion, the 3nd Bn. 50th Infantry, he put at Tinian Town alongside the remnants of Naval Guard Force there. Col. Ogata's battle plan and later efforts to implement it against US landings on Tinian help explain the large numbers of heavy weapons and dead Japanese infantrymen found by the Marines on or near the White Beaches before the sun set on Jig-Day And, when balanced against the 15 US troops killed ashore on Jig-Day, the nearly 1700 counted Japanese killed ashore on and around White Beaches in the first 48 hours after the sun rose on Jig-Day minus 1 is sure proof of the historic effectiveness of US Combined arms and its application before and during the Marine landings.

(Edit and move below section)

The appellation of 'genius and overwhelming effectiveness" on the American side of the Tinian operation is earned because Col. Ogata's 7 July plan for Tinian's defense was sensible and practical, well tailored to the hand he'd been dealt, and well executed during PHASE 2 of US operations against Tinian. Particularly so given the depleted state of his Naval Guard Force and the extraordinary challenges his remaining defenders then confronted, most especially those critical hours immediately before and after the Marines landed. For example, given the grim realities of US dominance of Tinian's daytime battle-space, Col. Ogata's 7 July order was impossible to fully carry out absent knowing well beforehand where the Marines would land on Jig-Day. This information the Americans successfully disguised to the point of workable ambiguity while other elements of their strategic plan also worked toward this end. This kept Tinian's defenders guessing despite America's very early disclosure of its intense interest in Tinian's north end and its beaches in the days leading up to the Marines landing there. In any case, Japanese mobility by day was limited to covert off road foot traffic under cover of high grown cane, dense thickets and woodlands. Road travel, nearly impossible in daylight, was extremely hazardous at night, and by now both were hobbled by lack of motorized transport. But the defenders were up to the task. Tough and determined, they knew the inland intimately, how to move around it covertly, being expert at camouflaged military maneuver, including with artillery and tracked armor. So it's likely that a good number of Col. Ogata's forces moved into the Mt. Lasso and White Beach areas well before Jig-Day. How else can we explain why US combined arms confronted far more enemy activity up north, including troop movements and fire from coastal guns and artillery hidden within the Mt Lasso and White Beach area than the American's had anticipated, enough to require US heavy counter battery and anti-troop ordinance well before and up to Jig Day? Or why the Jig-Day Marines found weapons within range of the White Beaches comparable to Tarawa's? Namely: 1/ three 140-mm. coastal defense guns, two 75-mm mountain guns, two 7.7-mm machine guns in pillboxes, 2/ a 37mm. covered antitank gun, two 13-mm AA / AT guns, two 76.2-mm. dual-purpose guns, and 3/ two 47-mm. antitank guns, a 37-mm. antitank gun, and five 75-mm guns? Or why those weapons were reinforced by heavily mined White Beaches? Or why 435 Japanese combatants lay dead within the Marine perimeter before nightfall on Jig-Day. Or why another 1245 Japanese were killed and counted there over the next 12 hours? The answers are obvious. Unlike at Tarawa, these weapons and men had been destroyed before the Marines landed and/or were so neutralized, stunned and disoriented that they were unable to mount a creditable (indeed hardly colorable) defense, much less a main force counter-attack, throughout Jig-Day. US Combined Forces, their plan and its execution, assured this. Still, given their valor and pre-arranged plan put into affect early on, well over 2000 Japanese would hit the White Beach Marines ashore hard in a three pronged attack long before dawn the next morning. But this counter-attack, however, was not only anticipated by America's plans (tactical, operational, or strategic) but generated by those plans that had been built on the US Commanders' judgement of their enemy's most likely response to the dilemma US Combined Arms forced them to confront. Thus the defenders were sucked into the pit of their destruction. See Footnote 1 (C).

Broadly speaking, within these two actions:

FIRST - how the US Navy, Marine Corps, and Army, working together, used ground breaking techniques in the deployment of revolutionary Combined Arms to shut down the Japanese defense of Tinian from dawn through mid-night on Jig-Day, and thus blasted open the space and time needed build a secure beachhead with minimal casualties amid what otherwise would have been impossible circumstances, and;

SECOND - how Tinian's Japanese defenders' husbanded and then marshalled their meager resources throughout America's onslaught to thereafter deliver a punishing counter-attack powered mostly by indefatigable will alone;

Between these two actions, one by each adversary, lay two remarkable achievements in the annals of war. And the profound consequences that flowed from America's seizure of Tinian, the US flights into Japan's heartland that ended the War in the Pacific, forever burnishes the legacy of those two events.

((( editing material)

A ----- By now US Combined Arms, operating from land, sea, air, and underwater (submarines) had cut off Tinian's defenders from ALL resupply (save for a dwindling few desperate landings on the remnants of Ushi Air Field and occasional covert small boat mad dash across the Saipan Channel). Now the Tinian's garrison's loss of a weapon, ammo, radio, medicine or other critical tool of combat most often neutered the combat effective of the those who manned them. Whole units collapsed. The airforce first. Airmen took to the hills, to hide. And, as stores of construction materials like concrete ran out, so did critical repairs to critical assets like revetments. Networks of defenses withered away daily, irrevocably.

B ---- This lethal choreography first choked off the remnants of Tinian's outside support, whether it come by sea or air, and thereafter took out the core of its defenses before the Marines landed on 24 July. It also magnified the power of those landings and their long and short term results until, ultimately, it was the strategic flights off Tinian that would break Japan's will to wage war even in defense of its home islands. The consequences of these collective efforts generated stupendous benefits for America. Those benefits, tallied up in all their variety and consequence, long and short term, against the price the America paid for those benefits, bestows upon the Tinian operation a unique place in the history of America's Pacific Ocean War against Japan.

((( editing material follows - Thus US Combined Arms in support of Amphibious Operations in the Marianas swung into action on 11 June and continued through 10 August as dictated by events throughout those islands, most particularly at Saipan, Tinian and Guam. At Tinian these combined arms ramped up with growing complexity and skill over 43 days, inflicting punishments that varied as they ebbed and flowed across an evolving battlefield. For example, this included periodic bursts as special missions dealt with emergent threats and opportunities until those bursts merged and flared into a long planned grand climax as the Marines landed on 24 July, only to thereafter ebb and flow again as the Marines' pushed east across then south down the island until it was secured on 31 July. This ebb and flow was notable for its innovative use and mix of widely variant, but mutually supporting, weapon systems as their means and methods of deployment became ever more tightly focused on getting the job done in the field through constant real time observation of threats and consequences that triggered continuous reorientation and adjustment to those rapidly changing circumstances that, in turn, refined follow on coordination of multiple combat actions in the field. This lead to cumulative and exponential results as US actions and their consequences evolved into what might be described as a series of ongoing loops and spirals of activities that, although tightly controlled, breed not only discipline and refinement, but also the rampant integration of variant weapons systems into collective action. Here individual initiative at times became free wheeling, novel and opportunistic. Over time this unleased creativity, new skills and novel solutions that merged for cumulative and sometimes exponential results, some whose long term consequences radiated far beyond Tinian. Meanwhile Tinian's campaign morphed into ever changing but continuously refined applications of fire that delivered differing types and combinations of munitions onto a wide assortment of targets in wildly different places and times, all day and night on Tinian. Some defenders, caught in a web of unrelenting surprise, dropped into a kind of suspended animation that choked and bewildered them as it also closed down their options and means to resist. Thus America shaped the odds and risks of its battle for Tinian to its best advantage while its battle plan served a myriad of tactical US objectives wrapped within a grand strategic purpose. Given the high quality of planning, coordination, and command, it's no accident that America gained at relatively small cost the singular platform it needed to bring an end to the Pacific Ocean War one year later. ---- more editing material -- Indeed, at Tinian, the highly effective and creative use of combined arms working within and outside of the landing maneuver itself, proved how successful amphibious landings can be achieved in otherwise impossible circumstances to great advangage.)))

PHASE 2 OF TINIAN CAMPAIGN: EDITING in PROGRESS BELOW as of DEC. 10 -

On 7 July, the Japanese high command, realizing that Saipan was lost to the Americans, shifted ultimate authority over its defense to the Japanese high command in Guam. Simultaneously, Col. Ogata, knowing that Tinian was next up on the US chopping block, re-organized his defenses on 7 July as stated, adding a more mobile roll for his infantry and artillery forces to compensate for his severely depleted fixed coastal defenses. Even then, however, he likely didn't anticipantte that the ferocity, effectiveness, and bewildering nature of the US artillery, air and naval bombardment had only just begun, with a particular and growing focus on Tinian's north end. Four more US Army artillery battalions, freed from missions against Saipan, were shelling the north end 24/7 by 8 July. By 15 July thirteen Artillery battalions on Saipan were focused almost exclusively on Tinian's north end. As US Gunfire ships along with land-based and sea-borne attack and bombardment aircraft now bombed and strafed Tinian at will, ranging up, down and across the entire island, delivering all sorts of ordnance in all sorts of places and manners, tearing at the fabric of the island's defenses. These combined arms, increasingly coordinated by Brig. General Arthur M. Harper's XXIV Corps Artillery, had begun the culmination of an intense and highly innovative climb. One that mixed and matched highly diverse off-shore air, sea, and ground capabilities, their tactics and strategies, and that over time took on a life of its own, melding all parts into a coherent whole, and increasingly effective holistic campaign that ebbed and flowed all over the island as its parts achieved cumulative and exponential effect. This joint endeavor reached a high watermark for the prepping of a battlefield in World War two. Not only did it find new and far more effective ways to degrade the enemy's ability to resist an amphibious landing, but also magnified exponentially the striking power, capabilities, and mystery of what otherwise would have been a weak and fatally hobbled assault over impossible terrain, to achieve singular results.

Thus, US commanders at Tinian integrated their supporting arms and their amphibious landing plans and techniques into a revolutionary whole, they re-invented in action modern sea-borne amphibious assault, not only the cumulative effect of integrated and mutually reinforcing supporting arms, but in how to integrate combined arms into innovative landing plans and techniques so they work in tandem to vastly expand the capabilities and options available to Amphibious Forces to confront and defeat a far wider variety of otherwise contested or "impossible" landings. A prodigy, and progenitor, the Tinian operation in 50 days evolved in the field to open up a myriad of possibilities for future elaboration and development for those willing to grasp them and thus write new futures for Warfighting generally, including amphibious operations.

Accordingly, with Saipan declared secure on 9 July, US commanders focused with finality on a critical and foundational issue, whether the Marines should land over the Tinian Town Beaches as demanded by Vice Admiral "Terrible" Turner (Joint Expeditionary Force Commander) or across the White Beaches and/or Yellow Beach as demanded by General Holland M. 'Howlin' Mad' Smith (Commander Expeditionary Force Troops). The controversy that had simmered for months came to a boil. The northern beaches defied then current doctrine. This did not deter Holland Smith. The Marine General was unwilling to forego Saipan's massed artillery and/or its potential. It could cover, reinforce, and enable ALL landings and follow on operations up north, breeding and thereafter radiating a myriad of opportunities and advantages throughout the entire Tinian operation, from start to finish. Thus, like the US Navy, but for somewhat different reasons, he directed his staff to begin planning the Tinian Operation concurrently with planning the Saipan operation well before they left Hawaii and, before they arrived at Eniwetok (10 June), his staff presented for his review their recommended plan for landing over Tinian's Northern Beaches. Surely that early plan, given earlier events on Tarawa and later events on Saipan, reinforced Holland Smith's long held belief that massed heavy artillery combined with intense and precise air strikes and naval gunfire directed by highly informed intelligence, all coordinated in tandem for cumulative advantage, could (indeed was essential to) assure his Marines a successful contested landing most anywhere, namely, one that best assured a secure beachhead with the best opportunity for MINIMAL Marine loses before the enemy could muster an effective defense and counter attack.

By now too Holland Smith's experience at Tarawa and Saipan had proven that such a result was not only required for ongoing tactical operational effectiveness, but also for strategic reasons, if only because it was a moral imperative for US Commanders. And that these lessons, when applied to Tinian, pointed to such a landing on its north end. There, for a variety of reasons, it presented the best opportunity to protect his Marines during their landing phase and thereafter could best help them to shatter any enemy main force counter attacks against the Marine perimeter established the first night and/or shatter any resistance to the Marines' later push across the island's north end to its far side, while it could also best enable his forces to equip and position that follow on Marine offensive maneuver to efficiently achieve its multiple objectives at the lowest cost, namely: decapitate the enemy's command and control atop Mt. Lasso, isolate Tinian's strategic north end, and destroy its key military assets and positions along the way, while it also seized Ushi Airfield to supply follow on operations. Of key importance, these objectives, as they were achieved, mutually reinforced one another, and so produced cumulative benefits that also radiated outward. Hence the Marines rode these cumulative benefits across the inland and then on their march south down the island to their final victory at its far end.

To accomplish these objectives, General Holland Smith judged that Marine light Infantry, supported initially only by offshore and overhead firepower, had to enjoy overwhelming fire support concentrated to destroy Tinian's defenders at the waterline and directly behind the beaches if they were to possess the best chance to gain the ground and time they needed to bring ashore sufficient personnel and the heavier weapons critical to building a defensible beachhead and to thereafter assemble all the tools and supplies they'd need to destroy all resistance to their push across the island. Only in this way too could his Marines, by landing up north, be best positioned to quickly and efficiently break the back of the enemy's defense of the entire island with minimal Marine casualties, while also leaving the Marines in possession of the prime real estate and resources they would need to drive enemy remnants pell mell south down the island until they could be trapped and annihilated at its far end. This, in a nutshell, was General Holland Smith's vision as it evolved for successful landings and following on ground operations within Tinian's north end.

But how did General Holland Smith and Admiral Harry Hill, working together, realize that potential in real time offshore and on the ground? Their first challenge was obvious. How could two full divisions land prudently across the tiny White Beaches and/or Yellow Beach up north? And, if not, what were the alternatives? Here again, Holland Smith's and Admiral Harry Hill's experience at Tarawa and Saipan, the obvious competence and sensibilities of both men, played important rolls in their later shaping of the more detailed plans for the Marines landing on Tinian. By early July both men saw no reasonable alternative to landings at Tinian's north end IF solutions could be found to the challenges posed by the northern beaches tiny size and exposed seaward location. For, in stark contrast to successful operations up north, landings down south at Tinian Town could well mark only the start of an unnecessarily long, roundabout, and bloody affair. It'd force Marines into an amphibious assault without massive artillery cover otherwise available. It'd force their assault over 2500 yards of a heavily mined beach-front, into the teeth of an expectant enemy, one that enjoyed long fields of crosswise fire from the flanks into exposed Marines in sea-borne transit who would then have to seize those mined beaches and fight their way through Tinian Town's urban grid. Here both men saw a repeat of the bloody Tarawa and Saipan's northern sector landings without the cause or excuse attendant to those earlier operations. And, from Tinian Town, Holland Smith's Marines next had to sever the island into halves at its widest part. In so doing, they'd have to destroy the remnants of Tinian Town and Marpo Wells defenders who would have retreated and holed up to the south of the Marines, to their rear. And simultaneously his Marines would have to wheel north to confront any enemy defenders coming south from Tinian's north end, BEFORE those same Marines could head north in earnest to engage as many as three fully intact enemy infantry battalions defending strategic assets, including their HQ within Tinian's north end. Plus, if only in their own defense, those same Marines had to do these multible tasks down south on three fronts BEFORE they reached the cover of Saipan's massed artillery. To Holland Smith, this woolly-headed and baggedy-assed monster of an operation traded Marine lives, critical resources and valuable time needlessly, and for little more than the logistic convenience (not necessity) of a harbor at Tinian Town while it foolishly delayed and complicated the Marines' central job of destroying the enemy's core decisively within hours after the Marines landed. Only by landing up north, could the Marines seize a beachhead that immediately threatened the enemy's only strategic real estate and military assets, thus allowing his Marines to decisively break the enemy's back within hours, not days or weeks. Another words, landing down south, despite its blood spilled, at best solved a naval logistic supply inconvenience, but little if anything more. In contrast, Northern Beach landings forced the enemy to break his own back trying to stop it within hours. Over by dawn the next morning, the rest was a mopping up operation.

So, if successful, the White Beach landing advantage was obvious. But so were its risks, unless addressed. The operation was otherwise riddled with known and unknown risks, novel challenges, and hidden paradoxes that demanded innovative solutions and counter measures while the Assault Forces operated, often under great pressure, within thin margins for error. These interactive risks and challenges lay within a single complex problem: How could two reinforced Marine Divisions gain the best chance to, by surprise, cross the tiny White Beaches intact and then seize, occupy and fortify a secure beachhead. One that could defeat a furious counter attack and then assure the logistical support necessary for a quick two Marine division push across Tinian that could seize Ushi Airfield, Mt. Lasso, and then Yellow Beach on Tinian's far side? Only then would the Marines have the best chance to quickly and efficiently destroy the bulk of the enemy's forces and its command and control center, whlle they also seized the island's only fully operational and strategic airfield three miles distant from Saipan, the one asset they critically needed to resupply the best knockout punch they could devise to eliminate what was left of a tenacious but defeated enemy: a Marine armored infantry charge down the island, clearing all resistance from coast to coast, including Tinian Town on its SW coast and Marpo Point on its SE coast, before the Marines annihilated enemy remnants dug into Tinian's rugged and highly defensible southern end.

Holland Smith's vision, its breathtaking ambition, was prescient and grand. But could his Marines prudently jump start all these possible advantages with so little initial access. Here he began by studying maps (topographic and hydrologic) plus overhead photos and intelligence earlier gathered. This study of available material revealed obvious challenges, and latent possibilities. As to the challenges: first, his initial assault had to cross unpredictable ocean currents then quickly mount and cross a wide and variable fringing reef. Only if successful at these initial tasks would that assault gain enough access to the highly irregular beaches and shoreline flanking those beaches to have a reasonable chance to overcome their second challenge, namely, to find sufficient passage onto, across and around the two tiny White Beaches that were 900 yards apart so as enable a division of Marine Infantry to seize and link up enough strategic ground within the rough corrugated interior behind those two beaches to have a reasonable change to build a defensible perimeter. Success at this third critical task, building a defensible beachhead within this perimeter, would require a difficult and complex series of follow-on maneuvers of supporting arms that could reinforce that perimeter into a secure beachhead as quickly as possible within the daylight hours of Jig-Day. Considered cumulatively, these operations presented a monumental challenge. One that piled a series of inherently novel, speculative, demanding, and consecutive challenges one atop another where any failure along the chain of interlocking pieces threatened to unravel the entire operation. Plus the Marines would have to achieve all these time consuming and inherently exposed maneuvers within the plain view of Col. Ogata's HQ atop Mt. Lasso surrounded by its defenses. Risky business, indeed. Here, where a single failure can unravel the whole, the chances for operational success are reduced exponentially, unless remediated. Could US commanders devise a interactive plan that broke this iron law of risk analysis? If so, with what, when and how? And if not, was landing at Yellow Beach a workable alternative or maneuver in support? Stated another way, what was needed to activate the latent possibilities hidden within the the north beach landings, and dilute the risks, bringing them within acceptable parameters.

To help find answers to these fundamental questions, General Holland Smith and Rear Admiral Harry Hill (Amphibious Assault Commander ) on 5 July ordered off and onshore reconnaissance missions of the northern beaches. These orders were issued despite Admiral Turner's earlier orders to stop all planning for any landing up north across the White Beaches and/or at Asiga Bay, so were a profile in courage given that Admiral Turner was Admiral Hill's direct superior. These night missions were done under extreme limitations. Their highest priority was to avoid detection and avoid capture so as to preserve the opportunity for tactical surprise on Jig-Day. Thus the covert swimmers were denied firearms, carried only knifes for self defense, and instructed to avoid whatever action risked capture detection. Such extreme stealth demanded the swimmers' silence and invisibility in the dark, and imposed conditions that hampered the swimmers ablity to fully collect and/or reaffirm the details of needed information on the fringing reef, the landing conditions along the shorelines, beaches, and ground otherwise inland from the water's edge. This produced qualified and subjective findings, but when combined with earlier intelligence, it brought the northern beaches (their challenges, feasibility and potential) into sufficient perspective and clarity for Tinian's highly experienced US Commanders to formulate workable base solutions for landings at the White Beaches and to discard plans for landing at Yellow Beach.

The Yellow Beaches recon mission carried out during the night of 10/11 July targeted two beaches within Asiga Bay. The mission against the northern most beach was aborted offshore when extreme enemy activity surrounding the beach threatened detection of the swimmers. The second team completed its mission and reported the southern most beach to be 125+ yards wide but tucked within high nearly impassible cliffs, save for a single narrow exit inland, bristling with guns and pillboxes behind the beach and fixed guns on both flanks. Floating mines, boulders, man-made obstacles, and pot-holes laced the bay waters directly off the beach. Double apron barbed wire infested the beach. Fortified gun revetments infested the Yellow Beaches' rear amid ongoing construction and enemy patrols. Landing there within Asiga Bay were deemed a last resort. The same night, on Tinian's far western side, powerful offshore ocean currents swept the White Beach 1 recon team past their targeted beach and carried it another 800 yards north until depositing the team onto a offshore reef from where it was later recovered. The same currents swept the White Beach 2 recon team past its beach and carried it another 900 yards before depositing the swimmers onto the reef fringing White Beach 1. From there the team conducted their reconnaissance of that beach. The next night (11/12 July) a recon team using a special radar / SCR-300 navigation finally got to White Beach 2. The White Beach swimmers's reports, when considered against the background of earlier collected intelligence on the beaches and surrounding areas lead to the following general information and impressions:

1/ White Beach 1 comprised only 60 yards of open sandy beach that allowed passage ashore for amtracs. This 60 yards of open beach-front was flanked at the shoreline on each side by another 50 yards of coral ledges from 1 to 6 feet high over the water, but broken in places by 'fairly wide" fissures that allowed troops irregular passage inland. Also in places here the Marines might be able to scramble overtop the ledges and thrash through thickets and boulders behind them until finding paths inland. Beyond these these lower 'inner' flanks, the Marines might find passage over higher outer shoreline ledges 6 to 10 feet high over the water for another 45 yards on both flanks.

2/ White Beach 2, 900 yards south of White Beach 1, included 160 yards of sandy beach. Only 65 yards of its sandy beach fronted directly on the water, allowing passage ashore by amtracs. The remainder of its sand beach, 95 yards, was rimmed at the waterline by coral ledges that rose from 1 to 4 feet over the sea for 45+ yards on each flank. Here, upright coral plinths and boulders 'studded' the sandy beach behind these ledges, thwarting access by amtracs. On each flank of White Beach 2's 165 yards of sand, more coral ledges rose from 4 to 6 feet above the sea. Here, along this shoreline, troops debarking their LVTs might be able to scramble overtop these outer ledges but then typically they also had to thrash inland through boulders and thickets until they found paths leading inland. So White Beach 2 had only 65 yards of open beach at its shoreline that allowed easy access onshore to tracked amphibious vehicles. This open center portion was flanked by some 330 yards of ledges accessible in places to troops who managed to scramble overtop those ledges then negotiate large boulders and dense thickets until finding the few paths and trails that led inland.

3/ So, COLLECTIVELY, the White Beaches totalled 125 yards of open sandy beach-front where amtracs could land and move inland, carrying Marine assault troops. The other Marines, those who arrived along the flanks of those two 'open' beaches more than 900 yards apart, had to exit their LVTS at the waters edge and scramble between or over ledges to get ashore then find paths inland that were few, forcing many on the flanks to scramble over inland boulders and through thickets to reach trails leading inland while they'd simultaneously had to kill or evade any defenders encountered if they were to survive their journey inland and thereafter join up with their comrade units so as to form defensible fronts and ultimately seize a perimeter. Even those Marines able to land on the 125 yards of sandy beaches accessible to amtracs at the waterline would find that their sand beach quickly evaporated into narrow paths that had to cleared and widened for tracked vehicles and heavy weapons to get inland. Here Mines were known to exist on White Beach 2, were considered "extremely" likely on trails behind White Beach 2, and had to be assumed to infest White Beach 1 until proven otherwise.

Thus the Marines had to confront a myriad of challenges posed by the White Beaches' difficult access, whether it be getting infantry, heavy weapons and supplies up onto, across, and exiting those beaches and their flanks and beyond them, so as seize enough additional ground inland to build a defensible beachhead. This raised a host of varied but interrelated problems. For example, absent innovative solutions, this difficult geography thwarted a blitzkrieg landing attack. Indeed, how could the Marine Infantry quickly land and build a unified front after landing on two tiny, irregular and mined beaches that were 900 yards apart and looked from the air to be separated by rugged boulder strewn thickets that well could be impassable in places? Plus, much of this ground was obscured from above by thickets that could conceal enemy defenses. Only a few paths, likely mined, appeared to lead inland. So, once Marine Infantrymen were able to seize the boundaries of a workable perimeter behind those beaches, how could they quickly aggregate inland the tracked armor, artillery and supplies they'd critically need to expand and reinforce that perimeter into a defensible beachhead? Here too the obstacles to success were cumulative. This heavy equipment and gear, each with its own special needs, capabilities and limitations, had to start their journey inland from the outer edge of a broad fringing reef offshore then transit all the way across the reef, beaches and coral rimmed shoreline before they could head inland to dumps and front line defenses, all within full view of enemy HQs and artillery pieces. These issues only highlighted problems. Innovative solutions had to be found to many subsidiary problems, large and small, that otherwise jointly or severally posed existential threats to the landings' success.

As if these threats were not enough, they were compounded by other complexities hidden off and onshore that could suddenly arise, as if from nowhere, to threaten the Marines and their plan of attack before, during, and after their Jig-day landings. A fringing reef beneath shallow water fronted both beaches and their flanks. Its width varied greatly, but averaged roughly 50 yards wide off White 1 and 150 yards wide at White 2, its large interior expanse was pocked with holes, and its outer (seaward) edge was deeply fissured in places, and its waters, particularly along its seaward edge, were often awash with powerful and erratic ocean currents and swells that swept in from hundreds of miles of the open ocean directly offshore, particularly in squally weather that typically arrived at Tinian's northwest coast long before approaching storms far out at sea made amphibious landings there impossible altogether. Complicating matters, Tinian's monsoon season was in full swing during. Unreliable weather was inevitable. The challenge for US Commanders was how to thread the needle between squalls, getting two divisions ashore for good, before a monsoon already forecast hit in earnest.

Beyond the vagaries of weather, more uncertainly lay ashore. Intelligence collection from US aircraft was plagued by the dense ground cover that carpeted locales critical to Tinian's defense, including corridors that spread south in several directions. Here Col. Ogata hid like snakes in a woodpile most all of his fixed and mobile artillery, infantry, tank, and anti-tank gun units, particularly those stationed in defense of the White Beaches and key high ground behind those beaches to and including Mt Mago, Faibus San Hilo Point, Mt Lasso and its HQ, as well as off road lines of covert transit east, west, and south that linked his defenses within Tinian's north end from the White Beaches and Faibus San Hilo Point on the NW coast to Asiga Bay on the NE coast, and points south to Marpo Hill and Tinian Town and beyond. Even in daylight, the enemy could move over these rough trails through and beneath thickets, woodlands, and seasonal high grown cane imperious to overhead surveillance. The fact that US operations were based on Col. Ogata's outdated June 28 plan of defense earlier captured on Saipan, and were unaware of his more flexible and mobile plan issued on July 7, magnified these blind spots.

Despite these challenges, after reviewing the recon reports on 12 July, US commanders overruled landings at Tinian Town down south and the Yellow Beaches up north in favor of landings across the White Beaches. And did so by finding creative ways to dilute the risks expected at the White Beaches to the point where the advantages gained by landing there outweighed the risks and costs of any alternative. In short, Holland Smith and Harry Hill forbid any landings across the White Beaches UNLESS AND UNTIL specified "strategic" solutions were put into place and/or achieved beforehand by the tactical commanders, so as to successfully override these challenges that would otherwise tip the scales against landing on the White Beaches. These strategic mandates (and rationales that drove them) included:

1/ Starting 13 July, there would be not less than 10 days of intense naval gunfire and carrier air strikes and Saipan based artillery shelling and air strikes before the JIG-DAY landings. As we shall see, these supporting arms in a variety of different, but mutually reinforcing ways, neutralized the major obstacles to successful landings on the White Beaches. For one of many examples, they degraded Col. Otaga's command and control atop Mt. Lasso, and would kill him and most of his staff on JIG-DAY.

2/ All coral obstacles and mines that would interfere with passage across both White Beaches were to be cleared before any amphibian craft mounted the beach so as to assure the quick passage of massed troops, tracked armor and supplies across and off the beaches into the fight inland.

3/ Two Armored Amphibian Tank Battalions would reinforce the 4th Marine Division. The 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion was to take the leading role. Its Company D, 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion was to lead the 1st assault wave against the White Beaches with its cohort Company C held in reserve for later JIG-DAY action. These amtank companies were deemed critical to defeat an enemy shoreline flank counter attack, either sea-borne or by infantry wading shallow waters just offshore. The amtanks had proven effective against such seaward attacks south out of Tanapag Harbor and Garapan on Saipan. Tinian's fringing reef's shallow waters that flanked the small landing beaches amplified this threat, particularly the rough area just north of White Beach I within easy reach of enemy at Ushi Airfield. A swale emptying onto that reef 75 yards north of White Beach 1 later compounded this threat.

4/ A US Army Engineering Battalion would reinforce the 4th Marine Division's Engineering Battalion to overcome the beaches limited access and otherwise expedite the landings and push inland by tank & Pack Howitzer Battalions reinforced by sister units detached from the 2nd Marine Division, and follow on logistics, including causeways and roads inland, to asssure that supply dumps be quickly established and filled inland behind the beaches for direct access and replenishment.

5/ A three day favorable weather forecast beginning Jig-Day was required to insure the landing of two full Marine Divisions properly supported by tracked armor, artillery and logistics and, if necessary, a pre-prepared air drop resupply from Saipan onto Ushi Airfield, should bad weather thereafter close down or limit resupply access to the White Beaches from offshore, and

6/ ONLY THEN could the 4th Fourth Marine Division land with 2 days supplies over the White Beaches, and 2nd Marine Division land on Jig-Day and/or Jig-Day plus One followed by a 2 day resupply for two infantry divisions on Jig-Day plus Two.

These mandates built the foundation under Tinian's planned Jig-Day Assault. In so doing, they magnified the access, cover, and surety for its approach and landing of light amphibious forces in small, multiple, time consuming waves. They also magnified America's ability to quickly aggregate firepower, mobility, armor and staying power in support of the amphibious troops once ashore. US commanders enhanced these results by threatening JIG-DAY landings over ALL Tinian Beaches. These threats diluted enemy defenses while it concentrated American power on two small points of entry and their flanks, blasting open otherwise impossible landing beaches. Other elements built into the plan worked in tandem for cumulative affect. The assault force was to seize an initial beachhead defined by an O-1 line that included the first high ground behind the landing beaches (including Mt. Maga some 2500 yards inland) so as to sieze command of the Landing Area. Then, on Division order, the assault force (reinforced by tracked armor) on JIG-DAY was to push inland and seize Mt. Lasso to command the heights overlooking the beachhead and destroy Col. Ogata's HQ atop those ramparts. This maneuver would cover the landing of the 2nd Marine Division and allow both divisions to then isolate Tinian's north end from its south by pushing east across the island to Asiga Point on its NE coast and south to Faibus San Hilo Point on its NW coast. This scheme, its elements, timing, and logistics, were designed to work synergisticly to counter the risks inherent in amphibious landings against contested beaches generally and, in particular, as they applied to the White Beaches, including the ubiquitous Murphy's Law. See Footnote 1 for details. These "strategic" findings and mandates issued by Holland Smith and Harry Hill dictated and ignited the high water mark of pre-invasion effort, innovation, and sophistication in the Central Pacific during the entire Pacific Ocean War. (Note: These mandates did NOT make surprise, or feign off Tinian Town, a precondition to the White Beach landings although the advantages of both were obvious from the start of Forager's planning in the spring of 1944. Instead, being tactical in nature and obvious in doctrine and practice, these decisions were left to the tactical commanders to decide, override, and adjust as circumstances shifted from time to time in the field.)

THUS:

By 15 July 13 US Army and Marine Artillery battalions with 156 guns were shelling Tinian's north end 24/7. On 16 July US Navy Task Force 52 gunships and airpower rejoined the 156 US artillery pieces that had been hitting Tinian's north end exclusively save for the few US Army Long Tom's that did occasionally reach down the island as far south as Tinian. Now too, US Air strikes off carriers and Saipan ranged across the entire island while the Saipan based Artillery focused on Tinians north end, and US Navy Cruisers and Destroyers began to hit specific targets that had proved unsuitable for Artillery and air strikes, all as coordinated generally by General Harper's XXIV Corps Artillery on Saipan.

So, begining on 16 July, special Naval gunfire missions commenced at 10 a.m. and continued to sunset daily, and Destroyers commenced their daily harassment of Tinian Town and vicinity at night. On 17 July, Destroyers began irregularly hitting enemy personnel madly trying to reinforce beach defenses in and around Asiga Bay at night and Saipan Artillery fired White Phosphorous shells into nearby Mt. Lasso's wooded slopes and caves reportedly sheltering enemy personnel. On 18 and 19 July, after US Artillery had exhausted its supply of White Phosphorous shells, two more destroyers joined the fracas, each sending 100 White Phosphorous shells into Mt. Lasso's and Marpo Hill woodland caves. Thereafter three destroyers fired 300 shells into caves sheltering personnel around Mt. Lasso and Marpo Hill for three consecutive days, 20, 21, 22 July, before harassing Tinian Town each night. US Army land based and Navy carrier based strike aircraft worked in tandem with this Artillery and Naval gunfire. This forced Col. Ogata's to feverishly work to repair and hold together his defenses around his Mt. Lasso HQs (including the Yellow and White Beaches on opposite sides of the island) as well around the Tinian Town Beaches on its SW coast. On 20 July a US Heavy Cruiser, using its secondary and main batteries, added to the mayhem. Its three day all day special fire missions hit hardened targets, enemy activity sites and targets of opportunity, daily. On 22 July a 2nd Heavy Cruiser joined the fray using its secondary and main batteries, and LCI (G) gunships hammered shoreline caves with 20mm and 40 mm cannon fire.

On 22 July Saipan's artillery barrage lifted briefly from the Yellow and White Beaches areas as US capital gunships and warplanes intensified their hammering of Tinian Town and Marpo and Gurguan Points down south. This firepower shift was to suggest that US main force landings would cross the 2500 yards of beaches at Tinian Town in lieu of a primary force landings across Tinian's northern beaches, despite the earlier artillery pummeling of Tinian's north end and the US assembly of a massive amphibious armada 3 miles distant from Yellow Beach within plain sight of Col. Ogata's HQ atop Mt. Lasso. US commanders had hoped to accentuate this bombardment disguise on 23 July. But at 0705 that morning a US observation plane discovered 3 heavy well concealed coastal guns at Faibus San Hilo Point, emplaced to defend the White Beaches, plus at least 14 anti-boat mines on White Beach 2. This revelation dramatically altered US bombardment plans, refocusing it on the White Beach area, particularly White 2, although the US Navy fire support fleet of 3 old battleships, 2 heavy cruisers, 3 light cruisers and 16 destroyers starting at 0600 continued to hit Tinian hard and often all day from every quadrant. 260 warplanes (fighters, bombers, torpedo planes) added to the mayhem.

So, on 23 July two battleships with destroyers off Tinian's SE coast pummeled the backside of Tinian Town. Two light cruisers off the island's SW coast hit Tinian Town's waterfront and high ground behind it and areas north to Gurguan Point. Destroyer Monssen, operating independently off the island's south coast, exploded an ammunition dump on Marpo Hill's north slope at 1052. Heavy Cruiser Louisville at 0600 began hitting known targets and targets of opportunity between USHI and FAIBUS SAN HILO POINTS, including those in and around the White Beaches. And the battleship Colorado, when notified at 0715, left its station off Tinian Town and sailed 6 miles north where, from 1240 to 1425, the Battleship concentrated 60 pin-point 16 inch naval gunfire rounds on the 3 shore guns defending the White Beaches and then joined the heavy Cruiser LOUISVILLE that had been hitting the White Beach area since dawn between a series of low altitude morning and afternoon air strikes against the White Beaches aimed to ignite the anti-boat mines on White 2. These airstrikes included afternoon US napalm strikes into woodlands SE of the White Beaches for 60 minutes before the heavy US gunfire ships renewed their shelling the White Beach area and Mt LASSO's western slopes that reportedly now also housed artillery emplacements and cave supply dumps, yet more disconcerting surprises for US landing forces. At 1700 1700 Louisville was given special mission to deliver 5-inch AA fire on artillery emplacements and cave supply dumps on Mount LASSO's western slopes 2500 yards east of Faubus Point. At 1720 the US napalm air strikes resumed against the White Beaches. This set brush and woods and newly exposed enemy positions aflame. At 1840 the Battleship COLORADO followed these air strikes with 40 air bursts to prevent the enemy's escape overland from the White Beach area.

Meanwhile, 2 US Cruisers with 3 destroyers in the Saipan Channel off Tinian's NE coast had been shelling Tinian's NE side from Ushi Point to Masolog Point, including the Yellow Beach area and Mt. LASSO's east side. All the heavy gunfire-ships retired at 1845, but the destroyers remained off Tinian, hitting road junctions leading to the White Beaches, harassing Yellow Beach and covering a UDT recon of White Beaches with counter-battery and neutralization fire before the ships harassed White Beach approaches north of MT. LASSO. US Minesweepers also swept waters off the White and Tinian Town Beaches.

Later Admiral Hill reported that: (TINIAN) ... had been methodically and almost continuously bombarded by air, artillery, and naval gunfire since the beginning of the assault on SAIPAN. All known dangerous enemy batteries and installations had been destroyed long before JIG Day...;

IN SUMMARY from 15 July through 23 July (Jig Day - One): US Navy ships fired some 27,000 shells at Tinian during this 8 day period. US artillery on Saipan fired another 36,750 shells, the vast majority hitting Tinian's north end. (Only 24 of Saipan's 156 artillery pieces could reach beyond Tinian's north end into southern Tinian that included Tinian Town.) Meanwhile, US planes sortied over the entire island daily, strafing and bombing. On 23 July US forces fired some 16,700 shells at Tinian. The Navy fired 6,700 shells that day. US artillery on Saipan fired another 10,000 shells at Tinian's north end, the location of Tinian's primary airfield, its two landing beaches (White Beaches), its command and control center atop MT. LASSO, and its Yellow Beach three miles away from America's 156 artillery pieces across the Saipan Channel. And where Col. Ogata, whose HQs commanded the heights between Yellow & White Beaches, had since 15 July a ringside seat atop a mount lit afire amid bedlam as he watched America arm and assemble a vast armada that would on JIG DAY breach his island fortress, kill him, and break the back of his army, all within 24 hours of its appearance off the White Beaches.

Since 15 July an naval armada for 15,800 shock troops, their weapons and critical supplies, had begun loading directly from Saipan's docks and beaches into landing ships and amphibious craft that slowly assembled at anchorage off Saipan into an amphibious task force and that would in the early morning hours of JIG DAY head in darkeness southwest in stages, each sailing around Tinian's north end, before it arrived behind a line of US Navy heavy gunships belching fire and steel from 3000 yards offshore the White Beaches. Each stage of this Armada on arrival off White Beaches would organize itself into a growing amphibious landing force. This would include 430 assault craft poised to pass through the gunfire ships and hit the White Beaches followed by 200 more landing craft carrying heavy tracked weapons before more amphibious craft carried critical supplies directly across beaches to dumps built inland by combat engineers in earlier assault waves. All of this was to be supplemented later in the day by a prefabricated pontoon causeway installed off each beach on Jig-Day to offload wheeled trucks from LSTs.

So it's no wonder that Col. Ogata, watching the nearby threat grow hourly since Mid-July, had then madly accelerated his reinforcement of Tinian's White Beaches and Yellow Beach. For, on 15 July, the 1st of 2 huge Landing Ship Docks (LSDs) began hoisting war supplies off cargo ships lying off Saipan's landing beaches. And the 1st 6 of 30 US Landing Ship Tanks (LSTs) also began loading for battle, hoisting cargo nets full war supplies from the pier in TANAPAG HARBOR. For the next 5 days these 30 LSTs and 2 LSDs filled their top decks with enough rations, water and ammunition to fuel two Marine Divisions for 3.5 days of fighting on Tinian. In addition, on 19 July, 9 pontoon barges were loaded with drums of gas from cargo vessels anchored offshore. (Another 5 barges would be loaded on Jig-Day, all to refuel LVTs and DUKWs during battle.)

On 20 July 36 Sherman Tanks of the 4th Marine Tank Battalion boarded 36 Landing Craft Mechanized (LCMs) at the waters' edge of Saipan's Red and Green Beaches. Each LCM with one Sherman then swam offshore before climbing into one of the two waiting LSDs. Landing Vehicles Tracked (LVTs) had been specially altered with ramps for tanks to surmount the coral walls that flanked the White Beaches. These also left Saipan's beaches and climbed into the LSDs. Up the beach two 2nd Marine Division infantry Regiments boarded Landing Craft Infantry (LCIs) that carried them to 6 Attack Transports (APAs) whose Higgins Boats (LCVPs) shuttled the Division's vehicles out to their 6 mother ships. This group on Jig-Day would sail first to Tinian Town where 22 of its Higgins Boats lowered from a single APA conducted its feign landing.

The 4th Marine Division began loading 22 July. Its 132 Amphibious Trucks (DUKWs) left Saipan's BLUE Beaches carrying 106 Pack Howitzers with ammo and crews to 7 LSTs anchored offshore. The 4th Marine Division's 3 infantry Battalions loaded the next day, 23 July, into 435 LVTs that swam from Saipan's beaches to board another 27 LSTs waiting offshore. Meanwhile the 4th Division's vehicles on Green Beach drove into 100 Landing Craft Vehicles and Personal (LCVPs) at the waters' edge. More boarded at the seaplane ramp up north at TANAPAG HARBOR. 88 loaded cargo trucks with 21 trailers drove into 10 Landing Craft Tanks (LCTs) while the Division's remaining Shermans plus a company of flame thrower tanks boarded 3 LCTs and 6 LCMs. Elements of the Shore Party engineer battalions also loaded into 2 LCTS at the seaplane ramp. At the pier across TANAPAG HARBOR, 4 LSTs hoisted 68 LVTA4s amtanks aboard. Each LSTs embarked 17 amtanks. The LST carrying 17 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion amtanks 1st wave of assault also took aboard the 4th Marine Division HQ group and HQ company, 14th Marines.

With loading complete at 1800 on 23 July, the assault force armada commanded by Admiral Harry Hill began to assemble at its anchorage off Saipan where it would await orders to move out for its next morning's assault onto Tinian's White Beaches. However the 46 LCMs that remained from the orginal 92 LCMs began loading at 0600 on Jig-Day. 41 of these LCMs took aboard 2nd Marine Division tanks at Saipan's Green Beach. 5 of these LCMs transit would the next morning after daybreak transit direct to Tinian's White Beaches, while the other 36 LCMs with their 36 Shermans would board the two LSDs on their return from the White Beaches Jig-Day morning. These Jig-Day daylight movements of heavy amphibious forces would further confuse Col. Ogata atop Mt. Lasso, suggesting a US landing on Yellow Beach on the NE coast t o envelop Col. Ogata's command post from both sides of the island. Why not? The American amphibious armada now in plan sight of Col. Ogata's command and control center atop Mt. Lasso included more that 700 amphibious craft.

(Insert more text here)

NOTE: EDITING below is ONGOING:

JIG - DAY 24 JULY

2 LSDs, 37 LSTs, and more that 100 smaller landing craft sailed independently to their station off the White Beaches. All were loaded with amphibious war machines and/or amphibious shock troops, and/or artillery and/or tracked armor, and/or their critical support personnel and battle supplies. They departed their anchorage off Saipan beginning around 0330. Most arrived off the White Beaches before dawn on Jig Day 23 July and began to organized behind the US Navy Gunfire ships that were already on station off the White Beaches. Indeed hostile action had already unfolded in the dark beneath Col. Ogata's Mt. Lasso HQ behind the White Beaches. This is when the destroyer ---- deployed a US Navy Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) that attempted to explode anti-boat mines that had been detected on White Beach 2 by an observation plane the day before. Adverse seas reported at 0516 aborted their mission. This dramatically altered the schedule and placement of US Naval gunfire and air strikes, shifting both heavily into the WHITE BEACHES, trying to ignite suspected mines.

Also at 0530 all 96 105mm howitzers, 36 155mm howitzers and 24 155mm guns on Saipan opened fire, concentrating it on and around the White Beach. US Capital Ships simultaneously hit the White Beach AREA. Battleship TENNESSEE shelled the 60 yard wide White 1. Battleship CALIFORNIA lacerated the 120 yard wide White 2. Heavy Cruiser LOUISVILLE blasted the 900 yards of shoreline between the White Beaches. At 0545 heavy cruiser INDIANAPOLIS with 5th Fleet Commanding Admiral Raymond A. Spruance aboard arrived from Guam and took under fire the coastal gun pillbox on Faibus San Hilo Point that defended the White Beaches. INDIANAPOLIS then shifted its fire to Mt. LASSO's western slopes, hitting troop assembly and transit areas, and Col. Otaga's HQ behind the White Beaches. Light Cruisers BIRMINGHAM and MONTPELIER also hit Mt. LASSO. BIRMINGHAM smashed its western slopes. MONTPELIER lit into its eastern slopes behind Asiga Bay. Battleship CALIFORNIA fired point blank into White 2, igniting 12 (?) secondary explosions. Battleship TENNESSEE then Heavy Cruiser LOUISVILLE sent 40mm volleys into White 1. Off Tinian's NE coast Heavy Cruiser NEW ORLEANS sent anti-personnel air bursts over YELLOW BEACH in Asiga Bay. As the sun rose at 0557 minesweepers began running their courses off both White Beaches.

Meanwhile ---

(INSERT MORE TEXT HERE)