GENESIS - Tarawa:

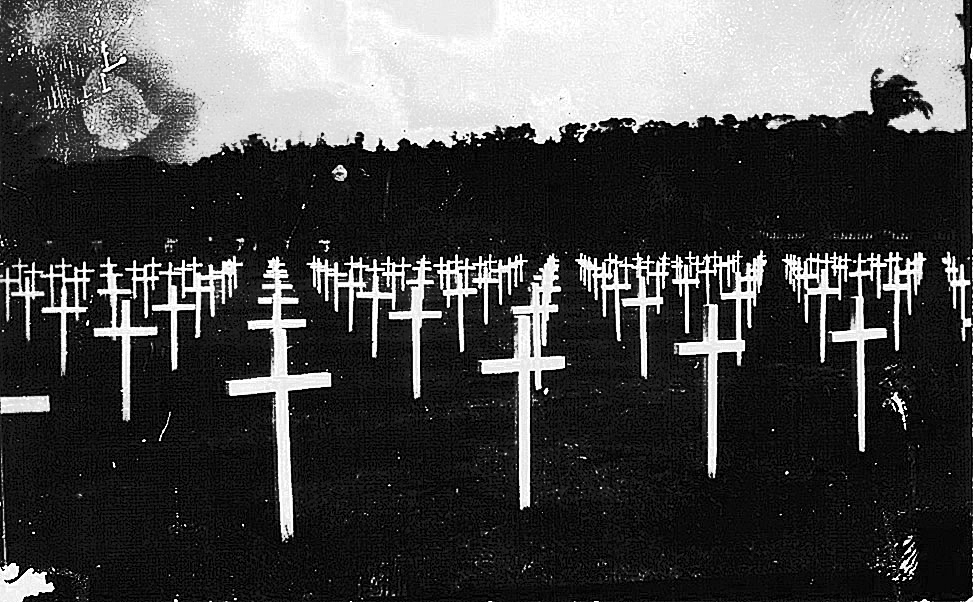

The 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion was specially designed during the Central Pacific Campaign. This 8000-mile seaborne thrust to the Asian rim began 20 November 1943 at Tarawa. Later, seeing the carnage where 6000 US Marines and Japanese warriors lay dead on Betio's 294 acres, General Holland M. Smith USMC, when asked how the Marines took the atoll, said: I don’t know. It was the most fortified place on earth, never seen anything like it.

One Japanese defender explained simply that: the Marines just kept coming.

Click to Enlarge p1General Smith wrote later: I realized then we were entering a new uncharted land... guided only by theory and peacetime maneuvers...and, on our first frontal attack on a fortified enemy atoll, we were ignorant of its capacity for resistance and of our own limitations... and I made up my mind that all future landings would be spearheaded by amphibious vehicles...and amphibian tanks, carrying heavier guns. 1/

Click to Enlarge p1General Smith wrote later: I realized then we were entering a new uncharted land... guided only by theory and peacetime maneuvers...and, on our first frontal attack on a fortified enemy atoll, we were ignorant of its capacity for resistance and of our own limitations... and I made up my mind that all future landings would be spearheaded by amphibious vehicles...and amphibian tanks, carrying heavier guns. 1/

Within days after Tarawa Marines began to assemble in the Boat Basin at Oceanside, CA., for an Armored Amphibious Assault Battation yet to be activated. Most were young, between 17 to 21 years old, recently enlisted to serve for the war's duration. Most had never been in combat. Now at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton they'd have 90 days to become a battation of 840 men who'd fight 70 amphibious tanks never before used in combat, leading shock troops into three epic battles of perhaps the greatest seaborne offensive in the history of war.

(For Central Pacific Campaign background see Footnote 2 below/)

BATTALION ASSEMBLES at Boat Basin between 1 Dec 1943 and 24 Jan 1944:

JERRY D. BROOKS: I was 15 when the Japs hit Pearl Harbor. Afraid the war would end before I graduated from high school, I got dad's permission and volunteered for the Marine Corps, after the 11th grade. Just 17, I'd never left Wichita, Kansas. So, headed west by train, I was amazed to see mountains and then the huge ocean. In San Diego, California, Marine NCOs met us at the train station. When their Marine Corps bus closed its doors, I was in the United States Marine Corps for sure. In Boot Camp at San Diego I listed my two top choices for advanced training as Paramarines and Raiders. My 3rd choice as Radio since my dad said that I'd learn a trade like he'd done in the Navy learning to be a barber while aboard the USS Nebraska in WW1. The Paramarines and Raiders disbanded before I graduated, so they sent me to radio school then advanced infantry training at Camp Pendleton. There, the place was so large and poorly laid out with hundreds of barracks willy-nilly on crooked roads and tent camps off in the boondocks, we sometimes got lost just trying to find its front gate. Coming in after dark from weekend Liberty, you could wander until sunrise trying to find your barracks. One day I saw a small sign posted on my barracks bulletin board saying: Volunteers wanted for Special Combat Unit. Everyone said it was hush-hush, being formed for immediate combat, just what I wanted. Me and a buddy signed up. Within 48 hours we were trucked to the Boat Basin at Oceanside. There the 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion was being formed up quick to fight after all the beach losses at Tarawa.

Note: Jerry Brooks wrote 47 illustrated letters home to his parents telling about his experiences at Marine Corps Boot Camp at Marine Recruit Depot, San Deigo, California. Click on Boot Camp Letters within the above Banner to see those letters and illustrations.

JAMES A. (AL) SCARPO: I came direct from LVT driver and maintenance School at Dunedin, Florida. There, one day outside the gate, we stood thumbing for a ride to St. Peterburg. A 300 pound man in a Lincoln Zephyr picked us up. How do you like your amphibian tractors, he asked. One of us said Their inventor should be in hell with his neck broke. The man smiled. Dropping us off in St. Peterburg, he invited us to visit his estate and use his pool while at Dunedin. He was Donald Roebling, the inventor of what we were learning the drive. This was the Donald Roebling I knew, said Battalion CO Reed M Fawell Jr. years later.

DONALD ROEBLING ESTATE, CLEARWATER, FLA. p3TOBY THOBE: Early amtracs often slipped a track crossing Dunedin's shallow bays, I taught students to dive in, find and reinstall the track. Dunedin was my honeymoon place before I helped set up the LVT school at Camp Lejeune, NC. I joined the 2nd Armored after Saipan. Seeing officers I'd earlier taught at Dunedin - Bill Manner, Basel Godbold, Dale Andrews, Lee Morrison & Quintin Hadwiger - felt like coming home.

DONALD ROEBLING ESTATE, CLEARWATER, FLA. p3TOBY THOBE: Early amtracs often slipped a track crossing Dunedin's shallow bays, I taught students to dive in, find and reinstall the track. Dunedin was my honeymoon place before I helped set up the LVT school at Camp Lejeune, NC. I joined the 2nd Armored after Saipan. Seeing officers I'd earlier taught at Dunedin - Bill Manner, Basel Godbold, Dale Andrews, Lee Morrison & Quintin Hadwiger - felt like coming home.

JAMES D. MACKEY: At Pendleton a notice went up: Wanted! Experienced tank men, drivers, other crew, all volunteers for new amphibious assault group. When Rose, Miller and I reported to the Boat Basin early, they sent us to a tent with a cot, two blankets, overcoat, a sea bag, and 3 Sergeants who put us through Col. Hanley's 3 week Raider physical combat training school. Now Boot Camp looked like a Sunday School picnic: bayonet and knife fighting then crawls through barbed wire under live fire during daylight followed by night marches hauling packs & weapons for 10 miles in 75 minutes at a half run/half swinging walk up and down hills without stop firing 30 & 50 ca. machine guns.

Click to Enlarge p3ADONALD B. MARSHALL - 5th Amphibious Tractor Battalion: "(At) Pendleton ... I joined a platoon going through Raider physical combat school. Col. Hanley headed it. He and 3 sergeants made us wish we were back in Boot Camp. We double-timed every place ... We navigated inflated rubber boats in pouring rain at night through a muddy swamp, we crawled under machine gun fire, set booby traps, learned jujitsu and knife and club combat ... and had to complete a ten mile run in an hour and 15 minutes. A Marine there from 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion, a sergeant named Mackey about 30 years old and hard as a rock, reminded me of Sgt. Allred. He never puffed. "If that old man could do it, I can," I kept telling myself. See AlligatorMarines.com

Click to Enlarge p3ADONALD B. MARSHALL - 5th Amphibious Tractor Battalion: "(At) Pendleton ... I joined a platoon going through Raider physical combat school. Col. Hanley headed it. He and 3 sergeants made us wish we were back in Boot Camp. We double-timed every place ... We navigated inflated rubber boats in pouring rain at night through a muddy swamp, we crawled under machine gun fire, set booby traps, learned jujitsu and knife and club combat ... and had to complete a ten mile run in an hour and 15 minutes. A Marine there from 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion, a sergeant named Mackey about 30 years old and hard as a rock, reminded me of Sgt. Allred. He never puffed. "If that old man could do it, I can," I kept telling myself. See AlligatorMarines.com

QUENTIN HADWIGER: An Oklahoma farm boy, I saw a sign: Wanted! Volunteers for Amphibious Tractors. Tractors gotta be right for me, I figured. But they didn't tell you those 'tractors' were the first wave. That came later.

MARSHALL E. HARRIS: My buddies and I at Radio School spotted the Wanted, all Volunteers sign after someone added in bold black letters: Combat Guaranteed! Seeing that, we signed up and told our friends who said: "Combat Guaranteed! that's B/S, tanks don't float!." Finally we convinced them that ours did, so lots of radio guys joined up with us, a very good thing given the huge shortage of radio operators in the Corps. (Note: Battlefield Radio communication, a burgeoning little understood new technology, was critical to tank warfare.)

RICHARD W. MASON: When the Raider Battalion was deactivated, our Master Sergeant said a special assault group was forming up at the Boat Basin. I got over there. First they sent me to an ordinance school: 50 cal. machine gun, rocket, etc. C. W. (BILL) GOODNIGHT: Just after we'd graduated from Jacques Farm tank school outside San Diego, the Colonel asked for volunteers to start something totally new, an amphibian tank battalion. We volunteered.

RICHARD W. MASON: At the Boat Basin, before the 2nd Armored formed up, Sleepy Adams showed me how to drive an amphibian tractor. Then I made Pfc and didn't have to fall in line when Sgt. Outen hollered: Privates outside! Now my rank meant something to me. Still, with only two blankets, I was cold at night even though we got an extra blanket after some officers arrived. So I still wore my long underwear from Idaho to bed.

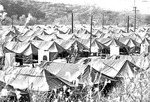

Click to enlarge G. Shirley, p4 G. MILTON SHIRLEY: A bunch of us were trucked to Boat Basin in early December. About 160 Enlisted Men were there but no officers. No one had the slighest idea what was going on. Feeble attempts at a 6 AM roll call produced maybe 30 people. Our tent was situated just right. If I slept in its front corner and heard my named called, I'd just open a hole in the tent and yell out Here!" I didn't even have to get off the cot. My mother sent me a Cake Full of Nuts for Christmas. Three of us on Xmas Eve sat feasting on Nut Cake and Limburger Cheese washed down with beer. Later I spent a lot of time using a brush to Stencil names on our gear until I got the bright idea of using a spray gun instead of a brush. It did the job much quicker. But when Major Williamson caught me, I thought I'll die with my boots on. Instead he said: "That's a damn good idea! Pass the word down the line to the rest of the men."

Click to enlarge G. Shirley, p4 G. MILTON SHIRLEY: A bunch of us were trucked to Boat Basin in early December. About 160 Enlisted Men were there but no officers. No one had the slighest idea what was going on. Feeble attempts at a 6 AM roll call produced maybe 30 people. Our tent was situated just right. If I slept in its front corner and heard my named called, I'd just open a hole in the tent and yell out Here!" I didn't even have to get off the cot. My mother sent me a Cake Full of Nuts for Christmas. Three of us on Xmas Eve sat feasting on Nut Cake and Limburger Cheese washed down with beer. Later I spent a lot of time using a brush to Stencil names on our gear until I got the bright idea of using a spray gun instead of a brush. It did the job much quicker. But when Major Williamson caught me, I thought I'll die with my boots on. Instead he said: "That's a damn good idea! Pass the word down the line to the rest of the men."

Click to enlarge Stallman p5TOM STALLMAN: At about 10 PM at the Jacques Farm tank school a Public Address system ordered me to report to Headquarters. There I was instructed to pack and leave for the Boat Basin by 11 AM next morning.

Click to enlarge Stallman p5TOM STALLMAN: At about 10 PM at the Jacques Farm tank school a Public Address system ordered me to report to Headquarters. There I was instructed to pack and leave for the Boat Basin by 11 AM next morning.

HARLAN ROSVOLD: After boot camp, I went to Jacques Farm, also near La Jolla, to the land tank school. We trained in the prewar light tanks and later in the M-4 Shermans. About the time I got comfortable and taking a liking to these medium land monsters, word came down that a new Amphibian Tank Battalion was being formed at the Boat Basin, near Oceanside, CA. Many of us were "volunteered" for this group. So later there, I'd start training in seagoing tanks much different from the Shermans.

JOHN L. LEWIS: When I arrived, Captain Bevans, the highest ranking officer, called me into his office and asked "could I handle an important job?" "Do my best Sir." "Okay, go to the PX and fetch me a carton of cigarettes." Then he was promoted to Major.

HAROLD C. MOODY: I went from Boot Camp into Amphibian Training at Oceanside. A Master Sergeant who'd come out of retirement ran things there always said: This is a hell of a way to fight a war. One morning he struck his head outside his tent, pointed into the distance and yelled at me: S-bird. See that hill? They're forming a new battalion up there. You've been wanting action. You'll get plenty with that group. Grab your gear and get over there.

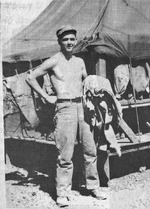

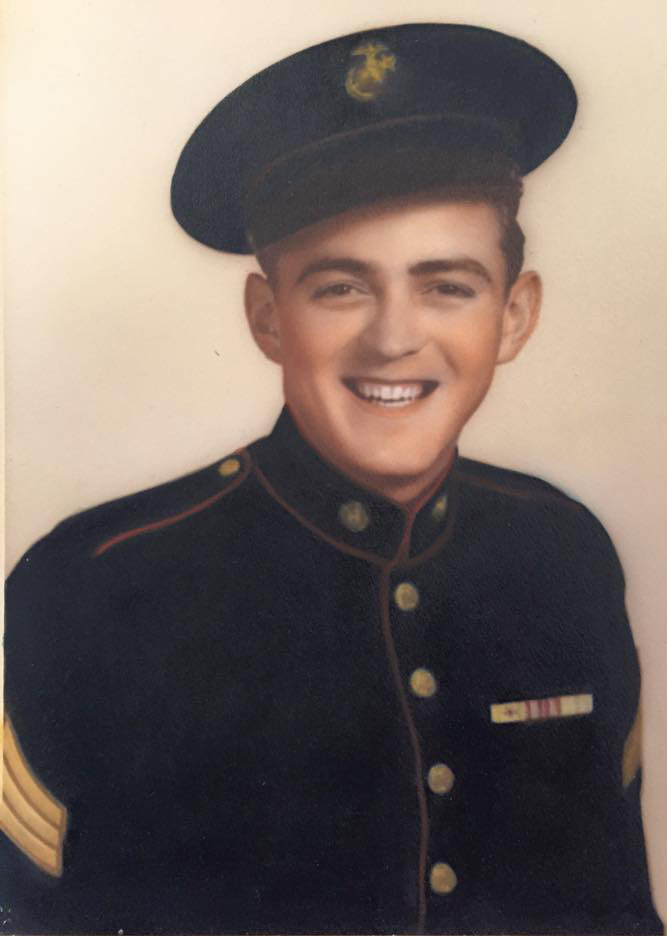

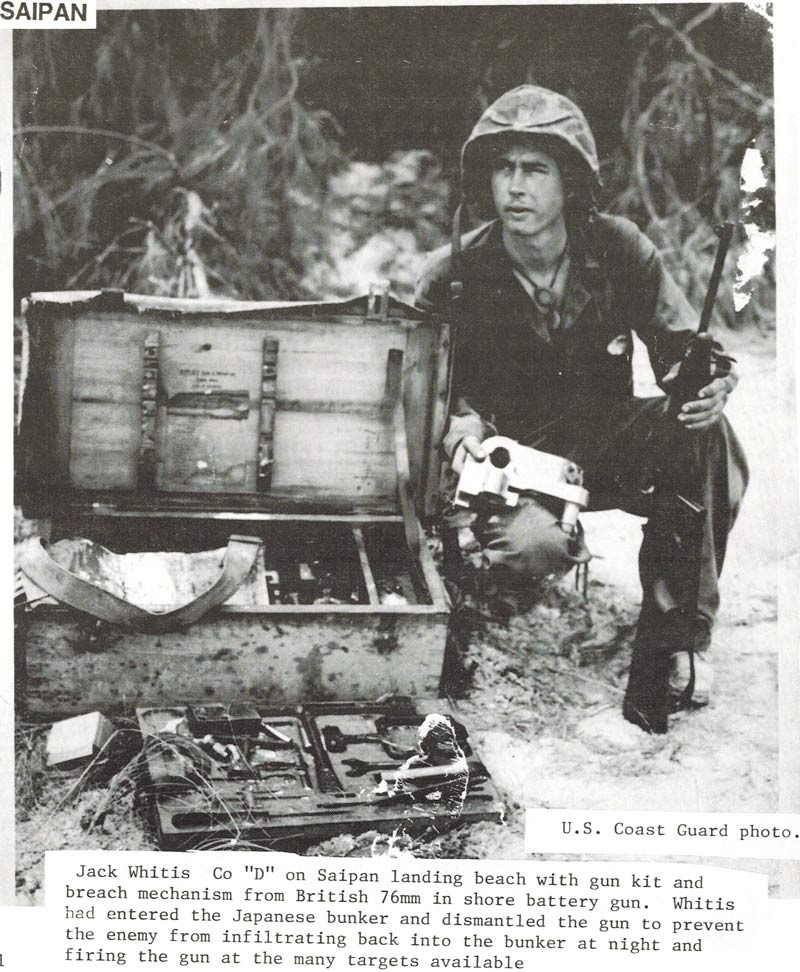

JACK WHITIS SAIPAN p6JACK W. WHITIS: At the Boat Basin I was sent to a class given by our Company Clerk Robert Rose on the 30 Cal. machine gun under Gunnery Sergeant John Liberatore's supervision. Fletcher Jones and I, caught goofing off, were ordered to field strip the weapon. Smart alecks fresh out of ordinance school, we stripped then reassembled weapon lickedly split while rattling off the name and function of each part. So impressed was Platoon Sergeant Wally Johnson, he had us circle the camp 3 times trotting at double time with weapons held high. We were really off to a great start with this new outfit.

JACK WHITIS SAIPAN p6JACK W. WHITIS: At the Boat Basin I was sent to a class given by our Company Clerk Robert Rose on the 30 Cal. machine gun under Gunnery Sergeant John Liberatore's supervision. Fletcher Jones and I, caught goofing off, were ordered to field strip the weapon. Smart alecks fresh out of ordinance school, we stripped then reassembled weapon lickedly split while rattling off the name and function of each part. So impressed was Platoon Sergeant Wally Johnson, he had us circle the camp 3 times trotting at double time with weapons held high. We were really off to a great start with this new outfit.

L. H. VAN ANTWERP: In Dec. '43 I was assigned to Maintenance Section. Ralph Bevans was our CO, Lee Morrison our Maintenance Officer. We had no Mess Hall so crossed a ravine into another camp to get chow. New people arrived every day, some from Dunedin's LVT School. At that early stage before our Battation CO arrived many of us were on an ego trip, and couldn't work together well. At night we had smokers and sometimes a too well attended Slop Chute.

CHARLES H. ORLOSKI p7CHARLES H. ORLOSKI: Restless at Pendleton I wanted more action. So the Post Troop Sgt. Major got me transferred to the 2nd Armored being formed to fight.

CHARLES H. ORLOSKI p7CHARLES H. ORLOSKI: Restless at Pendleton I wanted more action. So the Post Troop Sgt. Major got me transferred to the 2nd Armored being formed to fight.

HAROLD C. MOODY: The battalion had only one amtank, a few men, and hardly any training in how to drive it. GENE LEWIS: I joined from Pendleton's Radio School in February, we had a long way to go, not even close to a full complement of men and gear. We drove a few old LVT(A)1 tanks in and out of surf, none had a working radio.

JOHN C CRAWELY: In the fall of '43 the Boat Basin's Commanding Officer told me to round up 20 good men, go to Hawaii and drive four brand new LVT(A)1 amphibian tanks over the reefs there to see what they could and could not do. That fun duty lasted three months. Then I joined the 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion, a great bunch of Marines.

R. CARL SCHMIDT: On 2 Nov. 1943 Lt. Crawley took a small group of us to Oahu to experiment on how to blow a path through coral reefs for tanks using car inner-tubes filled with dynamite and other explosives. We always saved the day's last charge for a school of stunned fish that we then traded to the natives for drinks. We returned to the Boat Basin and joined the 2nd Armored on Feb 5, 1944.

JERRY D. BROOKS: I didn't get to Oceanside until March. This was after Boot Camp and Radio school at the San Diego Depot then Advanced Infantry Training at Pendleton. So in January and February at Pendleton, carrying heavy packs and rifles, we scampered up and down cargo nets hanging down the steel sides of ships. Never forget it. Offshore, with us combat loaded, we be hanging off and swinging around on the ropes dangling off sides pf ships, everything in our topsy turvy world seemed precarious - the tall high wall of the ship plunging up and down and high above little Higgins Boat bobbing alongside far below on a wind whipped ocean with us hanging high above with heavy packs and rifles dangling from ropes, all of us swinging and jerking and scrapping, going down the steel sided ship, toward the little open Higgins Boat bobbing below - and with everything moving in our vertical world it got scary and then it got more scary when finally with us trying to get into the Higgins boat that was still bobbing around us tethered to the ship, all moving in opposite directions; the crazy scene of moving steel parts threatened to catch us in between the ship's and boat's walls, crush a leg or more. And then, once we'd dropped abruptly into the Higgins boat, we had to climb back out, going up again into the air, dangling off ropes swinging from the ship still moving up and down on the waves. Finally we'd climb up over its top rail and onto its deck at last, exhausted.

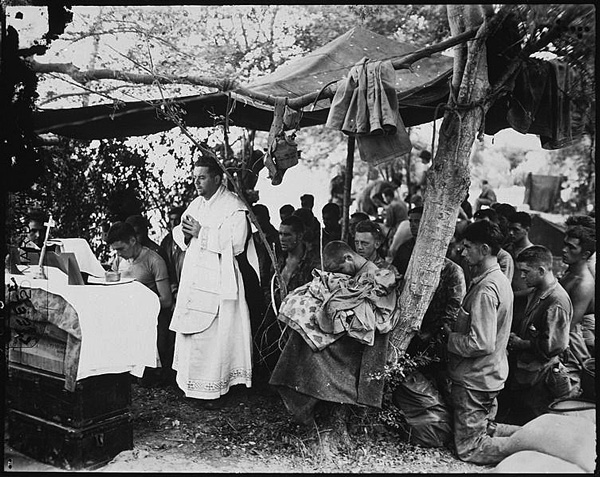

ORIE F. MORGAN: I graduated from Navy Corpsmen school with John H. Brady. He joined the 5th Marine Division and raised the flag on Iwo Jima's Mount Suribachi. I was on Iwo when the flag went up but unlike John I went onto the 2nd Armored after we graduated and detoured first to Saipan and Tinian. Most new Navy Corpsmen were sent to 5th & 6th Marine Divisions being built at the time.

BATTALION Activates & Trains at BOAT BASIN between 24 JAN and 26 APRIL 1944:

The Battalion's Headquarters & Service Company was activated 24 Jan 1944 when Lt. Col. Reed M. Fawell, Jr. arrived from the South Pacific where he'd served as CO, 1st Tank Battalion, 1st Marine Division. Unknown to Col. Fawell or the Marine Corps, his yet to be formed 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion's primary weapon was only a flash of inspiration in the mind of one man. Only days before US Army Col. William S. Triplet had a grand revelation. After he'd struggled through his waking, dozing, and sleeping hours ... with mental arithmetic, theories of organization, training problems, and tactical uses of amphibian combat ... Col. Triplet realized that the LVT(A)1 Amphibious Tank would be playing David versus Goliath ... throwing shot with the explosive power of a hand grenade (unless we got) a 75mm shell with 8 times the power. 3/ A fix was desperately needed. Col. Triplet's remedy dropped the open topped M8 75mm howitzer turret into the open body of a LVT(A)2 amtrac. This created an upgunned Amphibian Tank with 8 times the hitting power of its predecessor.

75 MM HOWITZER p8

75 MM HOWITZER p8 LVT(A)2 Click to Enlarge p8AIt's main gun (the 75mm howitzer) was test fired once in quiet offshore California waters in late February, 1944. Since the monster when fired didn't captsize, the Navy gave it a quick 2nd look then rushed it into production by the Food Machinery Corp in Riverside, Ca.

LVT(A)2 Click to Enlarge p8AIt's main gun (the 75mm howitzer) was test fired once in quiet offshore California waters in late February, 1944. Since the monster when fired didn't captsize, the Navy gave it a quick 2nd look then rushed it into production by the Food Machinery Corp in Riverside, Ca.

Meanwhile, at the Boat Basin, new recruits arrived daily, filling the ranks of the novel 840 man battalion with newly minted and just arrived officers who took charge of new companies and platoons being organized daily, until more senior officers arrived. Some learned to drive worn out LVT(A)1s. No one knew their training would be cut five months short. Or that they'd end up driving different machines. Ones just off drawing boards and assembly lines, revolutionary weapons with unknown capabilities, untested in manuevers or battle, leading the charge into a vicious island beach assault unlike any that had gone before.

(See PART D of Amphibious Tank Section for amtank Battalion's Table of Organization.)

Click to Enlarge p8BROBERT E. WOLLIN: On 28 January 1944 Marvin M. Cleveland, James R. McCarter, Philo R. Please and I reported for duty to Col. Fawell. All 2nd Lts we'd just graduated from Jaques Farm Tank School. Most of us had trained with land tanks, artillery or amphibian tractors. None had trained with LVT(A)1 amphibian tanks. Or heard of the LVT(A)4 we'd get just before battle. Our first task was to get the battalion's platoons and companies up and running. Col. Fawell put Please, McCarter and I in charge of starting Company A. Three green officers trying to jumpstart the beginnings of a brand new kind of fighting unit, we ran it as a 'Community Project. Kept our recruits busy with exercise, close order drill, and scurrying about getting physicals, teeth checked, scrubbing down, laundering up, fitted for boondockers and slotted into tasks.

Click to Enlarge p8BROBERT E. WOLLIN: On 28 January 1944 Marvin M. Cleveland, James R. McCarter, Philo R. Please and I reported for duty to Col. Fawell. All 2nd Lts we'd just graduated from Jaques Farm Tank School. Most of us had trained with land tanks, artillery or amphibian tractors. None had trained with LVT(A)1 amphibian tanks. Or heard of the LVT(A)4 we'd get just before battle. Our first task was to get the battalion's platoons and companies up and running. Col. Fawell put Please, McCarter and I in charge of starting Company A. Three green officers trying to jumpstart the beginnings of a brand new kind of fighting unit, we ran it as a 'Community Project. Kept our recruits busy with exercise, close order drill, and scurrying about getting physicals, teeth checked, scrubbing down, laundering up, fitted for boondockers and slotted into tasks.

JAMES R. MACARTER: Col. Fawell made 2 Lt. Bob Wollin temporary CO of A Company. 2d Lt. Pease got command of 1st Platoon. I got the 2nd and 2nd Lt. Nichol's got the 3rd. Our Company Maintenence officer 1st Lt. Cleaveland and I worked on getting a training schedule into operation. Using beat up Army DUKW's to do beach landings we'd come out soaking wet, wondering how we'd ever control the things during a real landing under fire.

(The first line Company, A Company, was activated 2 Feb 1944, 9 days after Col. Fawell's arrival.)

L. H. VAN ANTWERP: With Col. Fawell in command by February and most officers aboard, things got better organized. A month later (March) we'd started to become a real battalion, increasingly effective working in teams despite our training in beat up equipment. Next month we shipped overseas, in late April.

WINTON W. CARTER: With all the good food now our general belief was: This Commanding Officer must know somebody.

Gunny Roberts p9ROBERT C. ROSE (via Violet Rose): Once a month Gunnery Sergeant George Roberts came over to our Company Clerk's Office, sat down at our typewriter and went to work writing his wife. Every so often he'd ask where a key was, I'd show him and he'd continue typing. He'd take about an hour and I'd think he'd typed several pages, but he'd only managed a single small paragraph. Gunnery Sergeant Roberts had lots of patience in all things save for military matters. In matters of war, this man was trained and geared for action. When things got toughest in battle, he'd tell me: It's better than no war at all.

Gunny Roberts p9ROBERT C. ROSE (via Violet Rose): Once a month Gunnery Sergeant George Roberts came over to our Company Clerk's Office, sat down at our typewriter and went to work writing his wife. Every so often he'd ask where a key was, I'd show him and he'd continue typing. He'd take about an hour and I'd think he'd typed several pages, but he'd only managed a single small paragraph. Gunnery Sergeant Roberts had lots of patience in all things save for military matters. In matters of war, this man was trained and geared for action. When things got toughest in battle, he'd tell me: It's better than no war at all.

RAY SHERMAN: As Platoon Sergeants we took the men into the boondocks to keep them fit and do schools on tactics and small arms, Jap weapons and fortifications, gear care, and whatever came up.

LTV(A)1 Amphibian Tank p10 JAMES A. (AL) SCARPO: Our 1st job in maintenance was getting operational the few LVT's others had left behind. Among many problems, the breaker points in their magnetos had frozen in salt air. After we got the machines up and running, the Enlisted learned to drive in daytime, the Officers learned in the evening. The most critical skill was going in and out of the surf without being swamped or stalling out. But we learned in what we'd never use, LVT(A)1s. The much heavier LVT(A)4s with big 75mm Howitzer open turret gun arrived just in time for Saipan.

LTV(A)1 Amphibian Tank p10 JAMES A. (AL) SCARPO: Our 1st job in maintenance was getting operational the few LVT's others had left behind. Among many problems, the breaker points in their magnetos had frozen in salt air. After we got the machines up and running, the Enlisted learned to drive in daytime, the Officers learned in the evening. The most critical skill was going in and out of the surf without being swamped or stalling out. But we learned in what we'd never use, LVT(A)1s. The much heavier LVT(A)4s with big 75mm Howitzer open turret gun arrived just in time for Saipan.

LVT(A)1 p11ORIE F. MORGAN: In January Sergeant James R. (Pappy) Morris spotted me, a just arrived raw recruit medic walking the beach, and hollered "Hop aboard. As I dropped into the radioman's seat he headed into the surf. Gotta hit it straight," he yelled, plunging into a high breaker, "or she'll flip. And men drown." My knuckles whitened, holding on. Surfing a wave back onto the beach, he said, "If one track digs into sand first, it turns her over." Ashore with impish grin, he asked. "Want another spin?" "No!"

LVT(A)1 p11ORIE F. MORGAN: In January Sergeant James R. (Pappy) Morris spotted me, a just arrived raw recruit medic walking the beach, and hollered "Hop aboard. As I dropped into the radioman's seat he headed into the surf. Gotta hit it straight," he yelled, plunging into a high breaker, "or she'll flip. And men drown." My knuckles whitened, holding on. Surfing a wave back onto the beach, he said, "If one track digs into sand first, it turns her over." Ashore with impish grin, he asked. "Want another spin?" "No!"

Click to Enlarge p11AROBERT E. WOLLIN: Early on Col. Fawell told us to take Company A for bivouac training in the boondocks north of Oceanside. This mission in hindsight was good for us and the Colonel. It got us out from underfoot raising clouds of dust from close order drill at the Colonel's ever more crowded Boat Basin Camp filling up daily with newcomers that he had to form up into other companies.

Click to Enlarge p11AROBERT E. WOLLIN: Early on Col. Fawell told us to take Company A for bivouac training in the boondocks north of Oceanside. This mission in hindsight was good for us and the Colonel. It got us out from underfoot raising clouds of dust from close order drill at the Colonel's ever more crowded Boat Basin Camp filling up daily with newcomers that he had to form up into other companies.

Fortunately Gunny Sergeant Clarron T. Miller (who later won a field commission on Saipan) was assigned to help us. A day or two out one of our trucks fording a stream sank in quicksand at a spot within sight of where the Commanding General each morning and evening passed by going to and from his quarters in the hinderland. We labored for days, shoveling out the truck while trying to hide it from the General. A tank retriever finally hauled it out and Lt. Cleveland got the idea of field stripping then reassembling the truck. It's simple, we call it a training exercise for our maintenance section, making it good as new." His ploy worked. We got training reassembling it better than before. I escaped the brig for destroying of US Government Property. (This tank retriever may well have been operated by PFC James William Gabisch from Helena, Montana, who'd been trained for this job, along with tank transport and maintenance, skills and capabilities that would play important rolls in the upcoming battle for Saipan.)

Next we reported to the aerial gunnery range on the beach near Del Mar, CA. There a frightened pilot towed sleeve targets out over the water as we fired 50 Cal. AA machine guns at the targets floating behind his plane. I say a frightened pilot because we kept hitting his 50-100 yard long towing cable, severing it, dropping his targets into the sea. After this event Col. Fawell relieved me from command of Company A. Next I started up Commany D, tackling the job like a seasoned veteran, sure that I'd made and learned from all possible mistakes with A Company. (D Company was activated 1 March 1944)

JAMES R. MACARTER: Then 1st Lt. Platt took command of A Company and 1st Lt. Pickett became his Executive Officer.

CLICK TO ENLARGE p12CHARLES F. AMBROSE - COMPANY D: Capt. Handyside commanded D Company. I became his Exec. Trained for artillery and Carlson's Raider's, I didn't know amtracs but the Captain did. So did Lts. Wollin and Manner. Lt. Godbold was a near genius in tractor & tank maintenance. Warrant Officer Liberatore knew tanks and artillery. Handyside did a great job welding our diverse group into a team. We had 3 platoons and Company HQ Section. Gunnery Sgt George Roberts, one of the finest Marines I ever worked with, could really ramrod men. We had little equipment and didn't get into LVT(A)4 amphibian tanks until Maui then left so fast we had to be trained the tough way, in battle on Saipan. Photo shows Lt. Wollin on left with Lt. Thobe behind Col. Fawell.

CLICK TO ENLARGE p12CHARLES F. AMBROSE - COMPANY D: Capt. Handyside commanded D Company. I became his Exec. Trained for artillery and Carlson's Raider's, I didn't know amtracs but the Captain did. So did Lts. Wollin and Manner. Lt. Godbold was a near genius in tractor & tank maintenance. Warrant Officer Liberatore knew tanks and artillery. Handyside did a great job welding our diverse group into a team. We had 3 platoons and Company HQ Section. Gunnery Sgt George Roberts, one of the finest Marines I ever worked with, could really ramrod men. We had little equipment and didn't get into LVT(A)4 amphibian tanks until Maui then left so fast we had to be trained the tough way, in battle on Saipan. Photo shows Lt. Wollin on left with Lt. Thobe behind Col. Fawell.

LVT(A)1 p13RAY SHERMAN - COMPANY D: LVTs had been left by outfits before us, all beat up LVT(A)1s and troop carriers (LVTs) stripped of weapons. All we could do was run up and down the beach and go into the surf a bit. I don't recall any 37mm, 75mm, or 30 cal or 50 cal. machine guns at the Boat Basin.

LVT(A)1 p13RAY SHERMAN - COMPANY D: LVTs had been left by outfits before us, all beat up LVT(A)1s and troop carriers (LVTs) stripped of weapons. All we could do was run up and down the beach and go into the surf a bit. I don't recall any 37mm, 75mm, or 30 cal or 50 cal. machine guns at the Boat Basin.

(B Company was activated 15 Feb 1944; C Company on 21 Feb 1944)

JOHN ELOFF - COMPANY B: Right after I had arrived at Oceanside very late in the game, I came upon five Guadalcanal vets out on the beach putting a track on a just arrived LTV(A)4, only to learn they'd put it on backwards. Even at the tender age of 18 years old, I knew that even the old salts had a lot to learn about these brand new weapons.

Click to enlarge R. Rose p14DOUGLAS N. MILLICAN - H&S COMPANY: Able to type a little I became H&S Company Clerk. This included Battalion Headquarters, so I wrote up monthy what was happening to Everybody, and handled passes for Liberty. My buddy Bob Rose wanted to marry a church choir girl in San Diego. He needed all the passes he could get to pull it off, visiting with her. I helped him out. It worked. Violet became Violet Rose before we left. As the battalion grew, I knew it was a special outfit.

Click to enlarge R. Rose p14DOUGLAS N. MILLICAN - H&S COMPANY: Able to type a little I became H&S Company Clerk. This included Battalion Headquarters, so I wrote up monthy what was happening to Everybody, and handled passes for Liberty. My buddy Bob Rose wanted to marry a church choir girl in San Diego. He needed all the passes he could get to pull it off, visiting with her. I helped him out. It worked. Violet became Violet Rose before we left. As the battalion grew, I knew it was a special outfit.

BERNARD L. BLUBACH - COMPANY B: We trained at the Boat Basin with old Amphibian tanks with the 37 mm gun.

R. CARL SCHMIDT: Camp Pentleton's land tank Marines taught us engine maintenance, using amtracs that became wrecks.

JAMES D. MACKEY - COMPANY C: After I joined Company C in February, Sergeant Alex "Red" Schmidt trained me to drive Amphibian Tractors in the surf. I made Corporal in April.

WAYNE TERWILLIGER - COMPANY D: Drivers practiced taking their vehicles out into the breakers and bringing them back without stalling or being swamped. Among other problems, the huge waves pushed the tank sideways. This caused it to tip over. Our practice tanks had no guns, We couldn't train with those until we moved overseas to Maui.

JERRY D. BROOKS: I arrived in March and recall training without any amphibian tanks. Instead we spent a lot of time in Higgins Boats going through the motions of making assault landings while trying to get used to the waves so as not to get seasick. A seal took a liking to our Higgins Boat, and took great joy swimming underneath it, going back and forth, poppping to the surface on one side then the other, until after a while he let us reach out and touch him. When a "brave marine" threatened to bust the seals skull with his rifle butt, I threatened to put my rifle butt through the Adams Apple in the Marine's throat if he so much as touched the seal. Never did I understand why anyone would want to harm any such creature for fun. Anyway the seal kept doing his thing happily ever after as best I know. (Note: Jerry Brooks stood 6 feet 4 inches tall and became the battalion's boxing champ on Saipan)

MARSHALL E. HARRIS - COMPANY C: A bow gunner and radioman who sat up front next to the driver, I was trained to drive in and out the surf if the driver was hit. A key rule for hitting the beach was to down shift to first gear and hit the gas, revving up your RPMs, then pop the clutch just as you hit the beach. This put full power on the amtanks front treads, digging their grousers into the sand. Their purchase kept your amtank steady going straight ahead with maximum power despite the surf. Otherwise you might flip or be pushed sideways then flip. Later the technique got us up and over the reef at Saipan. Some of us had never driven a car and/or been out of state before joining the Marines. And here we all were now teen-agers learning to drive huge metal monster amtanks through breaking surf to assault fortified enemy beaches far out in the Pacific Ocean. We all grew up quick.

L. H. VAN ANTWERP - COMPANY C: By April the flower field and bridge outside our camp was well worn by us going on Liberty in Oceanside just outside our Boat Basin camp. I also got liberty to go south to San Diego and north to Los Angeles. Half of San Diego seemed covered with camouflage netting. The night trains to L.A. were blacked out with drawn curtains.

CHARLES H. ORLOSKI - COMPANY B: A mean Pony hung out in that field of flowers. Watch out, the bugger bites, I was warned. But going through a hole in the metal fence there and crossing the field was a half mile quicker into Oceanside than leaving through the Camp's front gate. So one night, coming back to camp in the dark carrying some goodies from town, I took my chances. I couldn't see the pony in the dark, but maybe half way across the field I sure heard the beast, galloping toward me. The race was on. Hoofbeats were pounding hard and gaining fast then suddenly right behind me running for my life when I tossed my goodies over the fence then dove for the hole. Then the HEADLESS HORSEMEN PONY hit it. Fortunately the beast was too big for the hole cause the fence metal stopped him. And I got away.

p16DALE G. WOLFRAM - COMPANY D: Married in April I overslept on the night bus back to the Boat Basin so woke up in Long Beach and missed 1st call. That restricted me to camp where I worked with Captain Handyside on packing gear during the day. He'd leave me off from work at my tent at 2000, and I'd sneak out of Camp through the hole on the fence along the railroad trestle to see my bride in San Diego. I didn't get much sleep those last 10 days before we shipped out, and suspect Captain Handyside knew what was going on. We lost a fine officer when he was killed on Saipan.

p16DALE G. WOLFRAM - COMPANY D: Married in April I overslept on the night bus back to the Boat Basin so woke up in Long Beach and missed 1st call. That restricted me to camp where I worked with Captain Handyside on packing gear during the day. He'd leave me off from work at my tent at 2000, and I'd sneak out of Camp through the hole on the fence along the railroad trestle to see my bride in San Diego. I didn't get much sleep those last 10 days before we shipped out, and suspect Captain Handyside knew what was going on. We lost a fine officer when he was killed on Saipan.

HAROLD C. MOODY: After Capt. Handyside learned that I'd been a Crawler Tractor Operator with the State Highway Department, he made me his tank driver.

TOM STALLMAN - COMPANY D: Leaving camp without a pass I was crawling under barbed wire at the trestle when Major Williamson spotted me. His dressing me down was so bad I wished he'd turned me in.

WAYNE TERWILLIGER: Going to Tijuana was a big deal. They warned us Be Careful. I went only once, to a little club with dirt floor and we drank a little and watched exotic dancers, but got back safe and fairly sober. Once, on overnight Liberty in San Diego, after my best buddy Paul Yarcho (from Lincoln, Nebraska) and I drank draft beer with raw eggs, we decided to get tattoos. Yarcho said "You go first." I plopped down 6 bucks and got my arm a big Marine Emblem but Yarcho refused doing his. I was pissed. Later playing Pro Baseball I never regretted my tattoo. People always noticed and asked about it . 4/

JERRY D. BROOKS: Before leaving Boot Camp at San Diego where we'd mingle with civilized folks again, we were shown a movie and given a lecture that scared me so thoroughly that I've never forgotten it's graphic discription and warning about Syphilis and Gonorrhea. When I say graphic I mean GRAPHIC in capital letters. If that lecture would not turn your stomach, nothing would. I think that movie kept a lot of us out of trouble. Later, while strolling around in Los Angeles, I came across a high school classmate from my hometown Witchita, Kansas. She'd left high school a year before me, after her tenth grade. Now here she was a year later working the street in Los Angeles. We were both embarrassed and parted quickly after a quick "Hi where ya been" small talk while I tried to pretend that I hadn't seen her soliciting at all.

MARSHALL E. HARRIS: Those early Navy TCS radios had 6 dails you adjusted to build up enough antenae load to switch to a different frequency for progressively greater ranges. We called it loading the antennae, working the whistle down to "Zero Beat" on each dial, we could bounce the transmission as far north as the big Navy Radio tower up near the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. WAVES worked the radios up there. So we spent a good deal of time working our radios trying to "pick up" female voices up there in San Francisco.

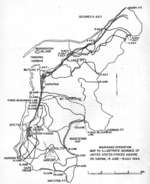

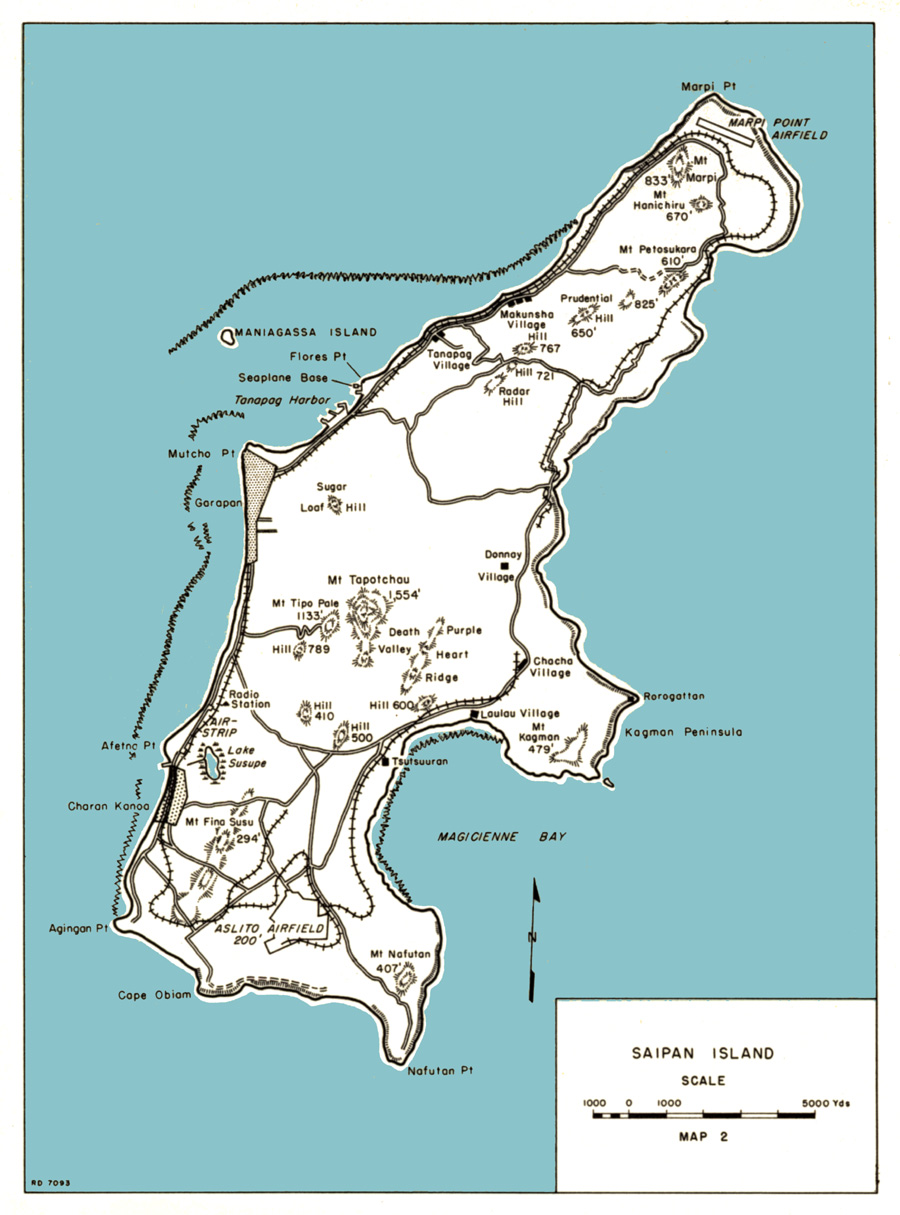

(Note: On 12 March, 1944, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander, US Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, to occupy the Southern Mariannas by 15 June, 1944, to "secure control of sea communications through the Central Pacific by isolating and neutralizing the Carolines and establishment of sea and air bases for operations against Japanese sea routes and long range against the Japanese home base." Thus sealed the Battalion's schedule for its first battle nearly 3 months before its men learned of its destination on their approach to Saipan. It's fate however was dictated largely by one man, Admiral Ernest King. In February, after Nimitz agreed with MacArthur to by-pass Saipan and abandon the Central Pacific by heading south to quickly merge the Central Pacific's Amphibious forces into MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Campaign, he received this rebuke from King: "The idea of rolling up the Japanese along the New Guinea coast ... and up through the Philippines to Luzon, as our major strategic concept, to the exclusion of clearing our Central Pacific line of communications to the Philippines, is absurd." Nimitz and his staff did an abrupt about face.

This was only one dispute in a long interservice struggle to sustain the Central Pacific Campaign of amphibious landings, including its centerpiece, the thrust of an alligator navy carrying Marine shock troops onto the beaches of the Mariannas, the linchpin to Japan's inner defenses. For details see Footnote 2a/)

BATTALION SAILS to MAUI between 17 APRIL and 2 MAY 1944

5 officers (inc. Warrant Officers) and 50 enlisted left for Mau as advance parties. The first of that group left San Diego on 11 April aboard the LST 131. Another sailed 14 July aboard the USS HAMMONSPORT that arrived at Mau 21 April. A third left 15 April on USS WILLIAM PEFFER. The USS ALCYONE carried the last advance party, sailing 17 April. The Battalion's main force comprising 29 officers (including 3 Marine Warrant Officers and 2 Navy Medical Officers) and 755 Enlisted sailed aboard the newly commissioned troop transport USS Comet. It sailed 26 July. Very few aboard the Comet, passengers or crew, had been to sea or war before.

CHARLES H. ORLOSKI - COMPANY B: Leaving the Boat Basin to go overseas, we hauled our many vehicles by Lowboy Truck down to the San Diego Naval Base. I had an extra man aboard my Lowboy to keep me awake, so made run after run around the clock. With the last one aboard and all squared away below, I went topside to wave goodby. All I could see was distant shoreline. (Without amtanks, we still had some 45 heavy vehicles.)

JERRY D. BROOKS: The stevedores had a work slow down going on at the San Diego docks So a bunch of us (I recall 23 from our Company) worked 6 hour shifts (each of us doing 6 hours on then 6 off) over and over until we'd loaded our ships to go to war, doing the work that the civilian stevedores who still on the docks were getting paid to do, but had decided to loaf instead, just when their nation needed them the most. I'll never forget that.

Also, getting a Battalion of Marines aboard a ship always seemed to overload the circuits of the officers. Say the General would set a boarding time of 8 am, well then each level down - the Colonel, the Lieutenant Colonel, the Major, the Captain and finally the Lieutenent - would each add some slack time into the schedule set by officer just above him to account of some expected or unexpected delay in stuff arriving from our camp or depot. As a result our last boarding instructions got us to dockside with field packs, seabags, and rifles two or three hours early where we'd have to stand around in the dark. But still for me it was a pleasure to board ship and leave the cold waters off the southern California Coast in April of 1944 and sail westward off to war.

Click to Enlarge p17AROBERT E. WOLLIN: On its maiden voyage the Comet left San Francisco (where it was built) to pick us up in San Diego. We boarded at 1310. Leaving dockside early next morning, some of us were already seasick. Most lined the rail for our last look at San Diego. Shoreline hustle and bustle came alive slowly in the early light. As we passed Point Loma, a voice from the Naval Station there carried out over the waters: Attention all hands, face the water, right hand salute, two, at ease and resume duties. Those salutes honored us going into combat. That's when we all realized that we were headed out into the unknown, and that many of us would not return. Later my wife wrote how she and many other wives and sweethearts stood on the hill there at Point Loma, in tears, watching us leave for war.

Click to Enlarge p17AROBERT E. WOLLIN: On its maiden voyage the Comet left San Francisco (where it was built) to pick us up in San Diego. We boarded at 1310. Leaving dockside early next morning, some of us were already seasick. Most lined the rail for our last look at San Diego. Shoreline hustle and bustle came alive slowly in the early light. As we passed Point Loma, a voice from the Naval Station there carried out over the waters: Attention all hands, face the water, right hand salute, two, at ease and resume duties. Those salutes honored us going into combat. That's when we all realized that we were headed out into the unknown, and that many of us would not return. Later my wife wrote how she and many other wives and sweethearts stood on the hill there at Point Loma, in tears, watching us leave for war.

Click USS Comet pg18L. H. VAN ANTWERP: Two days out in rough seas we renamed the Comet the USS Vomit or Puke. The Heads, troughs with wooden slots, were filthy. One of our guys down in the hole was in the brig. Guard duty there with no air circulation was awful. RICHARD W. MASON: The Troops Mess became a Chamber of Horrors. DOUGLAS N. MILLICAN: Most all was seasick. Sailors jammed the Heads. Marines hung over the railings, upchucking.

Click USS Comet pg18L. H. VAN ANTWERP: Two days out in rough seas we renamed the Comet the USS Vomit or Puke. The Heads, troughs with wooden slots, were filthy. One of our guys down in the hole was in the brig. Guard duty there with no air circulation was awful. RICHARD W. MASON: The Troops Mess became a Chamber of Horrors. DOUGLAS N. MILLICAN: Most all was seasick. Sailors jammed the Heads. Marines hung over the railings, upchucking.

VERNON C. LOWE: We called her USS Laybelow. We were sick, I mean SICK. SICK for 3 days, running topside to heave over the rail, only to be told to go LAYBELOW FOR DRILL. Amid the horror I'd heave into the latrine, run back up for air, going topside to heave then head back down, me and a lot of others too.

RICHARD G. PEDERSON: Marines lay stacked five high in close quarter bunks below decks, seasick. I couldn't eat, kept going topside to heave. KENNETH E. SMITH: One of our guys was so SICK he wanted to jump overboard, but didn't. He was killed the very first day on Saipan.

GENE LEWIS: I was SEASICK bad. 1st day I was afraid I'd die. The 2nd I was afraid I wouldn't die. ROBERT E. WOLLIN: Lee "Old Man" Morrison visited each junior officer, puffing his big black cigar, sickening everyone more. We wrestled him to his bunk, tied a life belt round his neck, inflated it with CO2 capsules then mashed his cigar into his face and mouth. Each zig and zag of the ship (trying to confuse any Jap subs lurking nearby) brought moans and misery.

At dawn 2nd day men were so SICK and dehydrated they couldn't move. We hauled them topside and laid them out like cordwood. In the fresh air Dr. Galuszka handed out magic pills and potions. The bilge pumps on the new ship didn't work, compounding the mess. Seas of vomit aboard slipped and slided everywhere. With mops we slopped the muck into buckets and hauled the vomit topside, hand-over-hand passing the overflowing sop up ladders in bucket brigades, spilling vomit everywhere, including back down into the hole. Philo Pease felt fine, however. He'd served in the Merchant Marine.

GENE LEWIS: The third day I had mess duty. I was fine after that.

ALBIN A. GALUSZKA - BATTALION MEDICAL OFFICER: Our Battalion had dedication and esprit de corps that was non pareil to any outfit. A case of meningitis in the Comet's crowded hold could have spelled disaster but each man's cooperation avoided one.  By Don C. Newey. Go to: dnewey.smugmug.com/History ( Col. Fawell credited Dr. Galuszka's quick diagnosis for keeping problem under control. Doc. Galusza was a hell of baseball pitcher, said Biff Crawley later. He helped make us undefeated Champs on Saipan, waiting for Iwo Jima".) On Christmas Eve, 1944 Col. Fawell on Saipan wrote his wife: The General's not happy. My Battalion just beat his whole damn Division, racking up 26 straight wins.)

By Don C. Newey. Go to: dnewey.smugmug.com/History ( Col. Fawell credited Dr. Galuszka's quick diagnosis for keeping problem under control. Doc. Galusza was a hell of baseball pitcher, said Biff Crawley later. He helped make us undefeated Champs on Saipan, waiting for Iwo Jima".) On Christmas Eve, 1944 Col. Fawell on Saipan wrote his wife: The General's not happy. My Battalion just beat his whole damn Division, racking up 26 straight wins.)

By Don C. NeweyAfter the storm eased and sickness passed, free time was spent loafing: playing cards or checkers, shooting dice, making music with guitars and harmonicas. Others sang, snoozed, watched clouds or hung over the ship's sides and fantail, dangling dungarees into the sea with long ropes, or watched seabirds float over the fantail or flying fish skip ahead of the bow waves as dolphins dived through them. Every so often US Navy loudspeakers blasted out:

By Don C. NeweyAfter the storm eased and sickness passed, free time was spent loafing: playing cards or checkers, shooting dice, making music with guitars and harmonicas. Others sang, snoozed, watched clouds or hung over the ship's sides and fantail, dangling dungarees into the sea with long ropes, or watched seabirds float over the fantail or flying fish skip ahead of the bow waves as dolphins dived through them. Every so often US Navy loudspeakers blasted out:

NOW HERE THIS, CLEAN, SWEEP DOWN, FORE AND AFT.

Then out came the sailors with water hoses and mops as Marines scurried away from the flushing water and sweeping sailors until the lazy topside routine settled in again

JERRY D. BROOKS: The sailors could hardly wait for the speakers to blare out "now hear this, now here this, clean sweep down fore and aft." Then they could work their firehoses to a fairthewell. With many so Marines topside, we got soaked. I never spent a minute below deck unless I had to, it stank of vomit. Fortunately we had the run of the ship. Hanging off the fantail, looking down, was a big deal: watching huge prop blades break through heavy swells of ocean far below. The Red Cross gave us little plastic portable chessboards. Each piece had a peg that fit in the hole in each square on the board. We didn't know chess so used them to play checkers. I learned a bit about shooting craps as I promply lost $20 a dollar at a time. That cured my fastasies of getting rich gambling. My only one lapse after that was losing $10 at Harts. I played my harmonica alot. I played its C note a bit high for singing but we managed anyway. Oftentimes on the fantail I played my harmonia all alone at night. Kaiser who'd never built a ship before, built our Liberty Ship in 30 days so it creaked and groaned as if to break apart especially when the waves started to whip up high. I was glad I hadn't joined the Navy.

Click to EnlargeJOHN ELOFF: I shipped out on the USS Hammondsport, a big ship with huge open hole in its center. Looking down into it you'd see a line of railroad cars. I also got seasick those first few days at sea.

Click to EnlargeJOHN ELOFF: I shipped out on the USS Hammondsport, a big ship with huge open hole in its center. Looking down into it you'd see a line of railroad cars. I also got seasick those first few days at sea.

CHARLES F. AMBROSE: Our LST disabled we laid over 12 days in San Francisco. This was a lucky thing. We got vital new equipment aboard that arrived way late, long after the rest of our Battalion had departed.

RICHARD MASON - COMPANY C: Our Advance party docked at Kahului before going to Maui. Ashore we stuffed ourselves with pineapples for 3 days before "the runs" ended the feast.

BATTALION TRAINS on MAUI from 2 MAY to 25 MAY 1944:

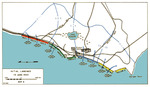

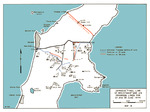

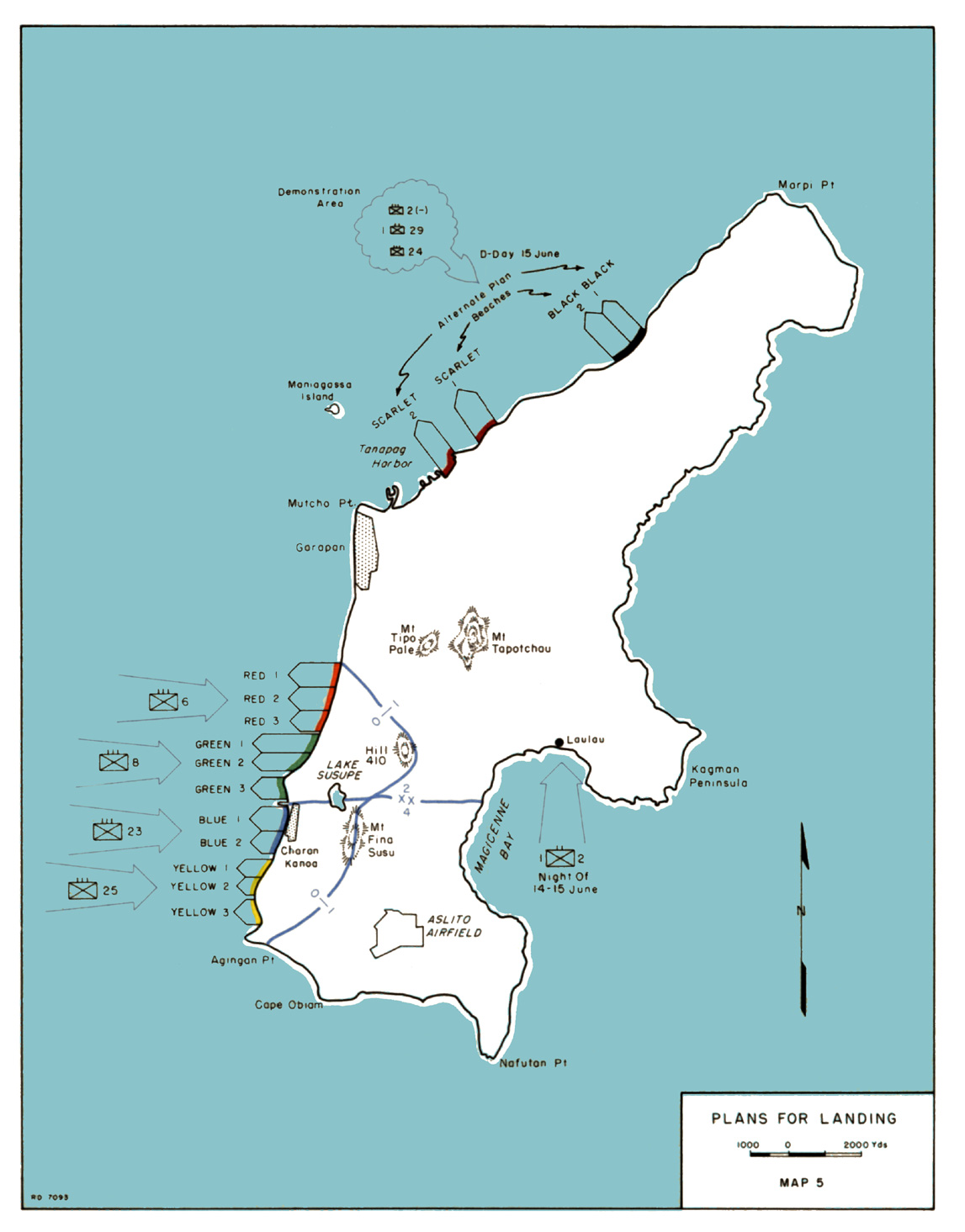

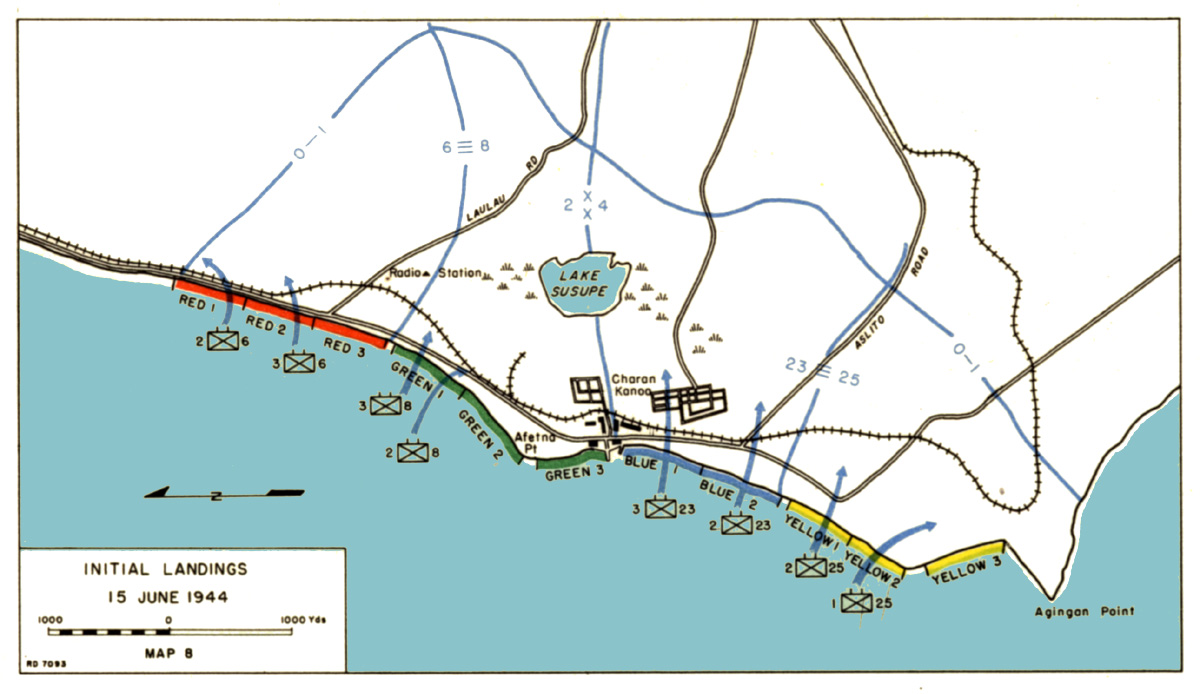

A handful of unarmed LVT(A)4s arrived the Boat Basin shortly before the Battalion sailed for Maui where it expected to find a full compliment of 70 LVT(A)4s and five months of training in their novel LVA(A)4s before battle. But aboard ship in transit Lt. Col. Fawell learned from his advance party in Hawaii that no LVT(A)4s had arrived for his battalion. He was again caught by surprise on 2 May when greeted on the dock by Col. David Shoup and Lt. Col. Wallace Green, Chief of Staff and G-3 respectively of the 2nd Marine Division. Will you be prepared to sail 12 May for maneuvers and on 19 May for combat action, Col. Shoup said. Despite this remarkable news, Lt. Col. Fawell replied YES SIR then handed Col. Shoup three pages of unmet requirements, including his "lost" 70 Amtanks.

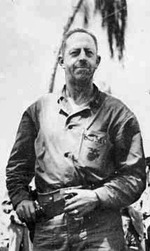

Col. David Shoup circa Tarawa p20

Col. David Shoup circa Tarawa p20 Gen. Holland M. 'Howling Mad' Smith, CO Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, & 5th Amphibious Corp Ashore Col. Fawell wired Gen. Holland Smith asking for air transport to Honolulu to pay his respects to the General at the earliest practicable date. He'd earlier served as the General's Aide-de-Camp. A plane flew him in the next morning. After a 30 minute meeting the General gave Col. Fawell a letter directing all commands to expedite all missing equipment to his Battalion. On 4 May 68 LTV(A)4s arrived unfit for battle, without armor, machine guns, radios, gun sights, periscopes & fire control systems.

Gen. Holland M. 'Howling Mad' Smith, CO Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, & 5th Amphibious Corp Ashore Col. Fawell wired Gen. Holland Smith asking for air transport to Honolulu to pay his respects to the General at the earliest practicable date. He'd earlier served as the General's Aide-de-Camp. A plane flew him in the next morning. After a 30 minute meeting the General gave Col. Fawell a letter directing all commands to expedite all missing equipment to his Battalion. On 4 May 68 LTV(A)4s arrived unfit for battle, without armor, machine guns, radios, gun sights, periscopes & fire control systems.

Armed with the letter Col. Fawell tracked down the Commanding Generals, Regimental COs and staffs of 2nd & 4th Marine Divisions disbursed around the Hawaiian Islands as he worked to unscramble a logistics and training nightmare by finding substitute gear for lost equipment, the expertize to install it and to train his men to use it. Meanwhile he educated Division and Infantry Commanders on the LVT(A)4's capabilities given that their May 3rd battle plan didn't anticipate using LVT(A)4s. See Note 5/. Major John I. Williamson , his Exec. Officer, and all hands up and down the line, had 5 days to prepare before they left for manuevers then battle. See Amphibious Tank Section and Note 6/ for Admiral Ernest J King's rationale behind accelerated schedule.

L. H. VAN ANTWERP: Most of us had never seen or driven our LVT(A)4s before Maui. Fresh off the factory floor, our amtanks lacked howitzer sight, armor plating, machine guns, radios, and most everything else, except notes left in them by factory workers saying stuff like Give the Japs hell! Fortunately, our Battalion CO was well known by top people like General Howling Mad Smith. He gave our Col. a carte blanche letter ordering all concerned to get us all the gear and outside technical help we needed. Suddenly lots of Army and Marine land tank and artillery people came in from the outside to help as we worked round the clock, getting our tanks and ourselves ready for battle.

MARSHALL A HARRIS: Our mechanics from Battalion HQ & Service Company swarmed like ants over those shell amtanks servicing and rigging them alonside outside tank and artillery people. As they finished rigging gear into the tanks, us guys who'd operate them in battle hopped in and started learning how the gear worked and didn't work. As bow gunner I learned things like how to remove and replace quick a hot barrel and reload from the ammo box so as to best feed rounds into a bow 30 cal. machine gun. The 75 mm ammo loader in the back compartment learned how to set cloverleaf ammo patches and fuse times for 75 mm shells. The turret gunners above them learned about the 75 mm turret traverse, manual firing by lanyard, etc. Ultimately we earned the basics of each other's jobs. That way we could operate effectively despite casualties. Amazingly, all this was done without instruction or tech manuals of any kind.

Maui Click to Enlage p21RICHARD W. MASON: We'd work around the camp then go to Lahaina to fire an alotted 5 rounds of 75mm ammo at targets. Then Major Bevans told us we'd leave for combat in 11 days. Crazy as we were, we thought that was great. The Major didn't think so. He'd expected six more months training plus we hadn't got gear we needed for combat, like 75mm Howitzer sights. It was a miracle that Col. Fawell, working around the clock, got most all we needed before our landing on Saipan. Few knew what Major Bevans did. Our real learning on how to fight in those amtanks would come in battle, fighting Japs.

Maui Click to Enlage p21RICHARD W. MASON: We'd work around the camp then go to Lahaina to fire an alotted 5 rounds of 75mm ammo at targets. Then Major Bevans told us we'd leave for combat in 11 days. Crazy as we were, we thought that was great. The Major didn't think so. He'd expected six more months training plus we hadn't got gear we needed for combat, like 75mm Howitzer sights. It was a miracle that Col. Fawell, working around the clock, got most all we needed before our landing on Saipan. Few knew what Major Bevans did. Our real learning on how to fight in those amtanks would come in battle, fighting Japs.

CLICK TO ENLARGE p22From May 5 to 11 the Battalion worked madly rigging shell amtanks. It installed fire control systems, radios, armor plate, gun mounts, shields & sights. Rogue gear had to substitute for what hadn't arrived. Men had to service brand new amtanks without manuals and then learn the amtank's capabilities and limitations in combat. Stuff like how to launch it off LSTs into the sea, drive it in formation through open ocean, over reefs, across lagoons, onto beaches then inland under enemy fire while returning fire. How to make it do what it could do, and avoid doing what it could not do. These skills critical to their mission and survival had to be learned in a war machine never used before. Ones unlike earlier models, and under conditions unlike what they'd confront on Saipan, an amphibious assault unlike any that had done before.

CLICK TO ENLARGE p22From May 5 to 11 the Battalion worked madly rigging shell amtanks. It installed fire control systems, radios, armor plate, gun mounts, shields & sights. Rogue gear had to substitute for what hadn't arrived. Men had to service brand new amtanks without manuals and then learn the amtank's capabilities and limitations in combat. Stuff like how to launch it off LSTs into the sea, drive it in formation through open ocean, over reefs, across lagoons, onto beaches then inland under enemy fire while returning fire. How to make it do what it could do, and avoid doing what it could not do. These skills critical to their mission and survival had to be learned in a war machine never used before. Ones unlike earlier models, and under conditions unlike what they'd confront on Saipan, an amphibious assault unlike any that had done before.

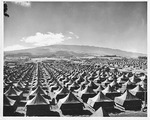

Click Camp Maui 1945, p22AROBERT E. WOLLIN: Our Maalaea Bay tent camp had no electricity or water, just outhouses. Trucked in water fed troughs for washing and open showers. We used daylight to best advantage, prepping our new amphibian tanks and ourselves for combat. We did firing practice and driving in formation, going in and out of the Bay, getting the feel of entering the water, turning about, and clamoring back on land. Lots of shifting and good timing by the driver were needed to hit a wave just right going over a reef so we moved through water in 5th gear then touching land we down shifted and revved the engine, grinding onto the sand. These were critical skills, a stalled amtank is a sitting duck for enemy fire. But our strange new vehicles worked and acted differently than earlier models. And we had to practice without combat loads so didn't know how the added weight would affect their mobility. We assumed we'd float after rolling off an LST into the sea. And had no idea of the terrain we'd face on Saipan or real practice in how to deal with it.

Click Camp Maui 1945, p22AROBERT E. WOLLIN: Our Maalaea Bay tent camp had no electricity or water, just outhouses. Trucked in water fed troughs for washing and open showers. We used daylight to best advantage, prepping our new amphibian tanks and ourselves for combat. We did firing practice and driving in formation, going in and out of the Bay, getting the feel of entering the water, turning about, and clamoring back on land. Lots of shifting and good timing by the driver were needed to hit a wave just right going over a reef so we moved through water in 5th gear then touching land we down shifted and revved the engine, grinding onto the sand. These were critical skills, a stalled amtank is a sitting duck for enemy fire. But our strange new vehicles worked and acted differently than earlier models. And we had to practice without combat loads so didn't know how the added weight would affect their mobility. We assumed we'd float after rolling off an LST into the sea. And had no idea of the terrain we'd face on Saipan or real practice in how to deal with it.

Despite the hectic pace we'd top off each day's training with a swim. Beautiful fish swam in abundance and shone blue and crystal clear over sea urchins bright on coral reefs 50 feet below. Maui flowers bloomed ashore, the scent magnificent, especially at sundown as wind quieted just before the blossoms closed for the night. Our living then felt like Hog Heaven. Compared with what was to come. Our four line Companies, each with 17 amtanks, were up to strength at last, and we were altogether, working hard. Captain Handyside commanded our company, his Exec 1st Lt. Ambrose. 1st Lt. Manner led 1st Platoon with 1st Sgt Livesy his acting Platoon Sgt. I led 2nd Platoon with Plt Sgt. Sherman. Warrent Officer Liberatore led the 3rd Platoon with Sgt. Johnson his Acting Plt. Sgt. 1st Lt. Godbold served as Maintenance Officer extraordinaire assisted by Sgt. James A. Scarpo. But Gunnery Sgt. Roberts in his unique way really ran the company, the one who could always be counted on to get the job done.

JAMES A. (AL) SCARPO: It was a busy time. Most of us had yet to drive our new Amtanks. Only people from outside artillery units knew anything about its 75mm howitzer. Much key gear was still missing, such as gun sights. We had to fix this while our 6 months for training turned into less that 3 weeks to move into a new camp, fix our tanks, learn to use them then pack up, sail to maneuvers, do maneuvers then pack up and leave for battle.

VERNON C. LOWE: On Maui we first saw what our tanks looked like: pretty good. But some worried about their flimsy sheet metal sides, so we welded on armor plate there before we left.

JERRY D. BROOKS: I recall seeing about 70 or 80 of these big beauties on the beach waiting for us. They came equipped with 75mm howitzer in an open turret and a ball socket mount for a 30 caliber machine gun at the right front for use by the radio operator. Our H&S Company welded on each amphibian tank a swivel mount on the left side of the open turret for a 50 caliber machine gun and another mount on the right side for a second 30 caliber machine gun. This rig altogether later gave us a lot of firepower to clear hostile beaches. We spent a lot of time practicing forming a line abreast and moving together as a battalion toward our beach in Maalaes bay on Maui, and fired all our weapons a lot at a small island offshore. We were fairly accurate firing the 75mm from a stationary beach position. I don't recall that we ever tried to fire while moving.

CHARLES F. AMBROSE: We did all we could to get the new amtanks combat ready, adding armor, machine gun mounts, etc. Our Gunners got enough direct fire practice with the 75mm howitzers to become very accurate at a standstill from ranges of up to several hundred yards. We didn't have enough time to train as indirect artillery fire batteries.

MARSHALL E. HARRIS: Our tent was pitched at the far end of our camp at Maui and it faced the ocean. The scene was amazing. At night, after things had settled down, for a kid who'd first seen an ocean only only months before, I'd lay in the dark listening to surf roll onto a Hawaiian island just out my front door. During the day we'd go offshore and head north up the coast past Lahaina. Up there the whales were plentiful, so we had clear instructions: stay on the lookout, never get closer to a whale than 100 yards. Where the surf off the beach was particularly high coming in from the north, we'd practice driving in formation landings onto the beach, and then do manuevers onshore and inland. We'd have lunch inland. Once, I spotted several milk cows and look Jerry Swab over a fence to milk a cow. From Chicago, Jerry didn't know better, so I told him to hold the cow's tail out behind his rear end, otherwise the cow couldn't give us milk. Swab did as instructed as I got two cups of milk, one into each of our helmets. Once back with the guys having lunch, I told them how Swab had done all the hard work, keeping that cow's tail out of way of our getting warm milk. Everyone got a big laugh, except Jerry who insisted he hadn't been fooled, just played along.

JAMES D. MACKEY p23 RAY SHERMAN: All we could do was direct fire on targets that we could see and aim at. JAMES D. MACKEY: We prepped our brand new amtanks as best we could for combat. This included welding more armor plate particularly in front, and gun mounts for 30 caliber machine gun(s) on the open turret. We practiced driving our tanks in formation on maneuvers from shore to ship and back to shore. We fired our tank weapons.

JAMES D. MACKEY p23 RAY SHERMAN: All we could do was direct fire on targets that we could see and aim at. JAMES D. MACKEY: We prepped our brand new amtanks as best we could for combat. This included welding more armor plate particularly in front, and gun mounts for 30 caliber machine gun(s) on the open turret. We practiced driving our tanks in formation on maneuvers from shore to ship and back to shore. We fired our tank weapons.

GENE LEWIS: I saw our LVT (A) 4 tanks for the first time at Maui. I practiced working the radio, cranking it up, learning to find and stay on frequency, and we talked to one another over the radios between tanks, but not that much. The radio man's other responsibility was keeping the Amtanks' battery charged, as we'd sink without its power. It was a frantic time for everyone. I don't recall maneuvers with 2nd Marine Division, only picking some of them up on the Big Island, Hawaii, before we left for Saipan.

JERRY D. BROOKS: We were confined to our small area. I don't recall being able to leave our campsite except to a little country store mile down the road. Over 2/3's of Maui's people were of Japanese descent or born in Japan so there were too many to 'isolate" as in California, yet no sabotage occurred throughout the war as I understand it.

MARSHALL E. HARRIS: That little country store called Kihei Store was run by a Japanese family, a mom, dad, and 5 year old son. They were nice as could be to us. We'd buy soda pop there, go out on the beach, and sit on a log, drinking pop, watching the waves come in. In the 1970's I returned with my family. The dad had passed away, but his son who ran the store called his mother and we all had a reunion.

From 11-14 May the BATTALION loaded for maneuvers with 2nd Marine Division on 17 May.

p CHARLES H. ORLOSKI: I kept a small book and transposed my notes into a diary. Here's my 11 MAY ENTRY: AM to board APA 166 and transfer to LST; 13 MAY: Maneuvers about to start. First group with amphibian tanks boarded LSTs. Equipment carried: rifles, carbines, belts, canteens, pack, 2 clips, 125 rounds of ammo, 2 sets dungarees, 4 pr socks, 1 pr underwear, helmet, 2 pr shoes, 1 45 cal automatic with 80 rounds ammo, horseshoe roll w 1 blanket & mosquito net, head net, gas mask, knife, mess gear, poncho, extra shoe laces, camouflage head gear, toilet articles. 17 MAY: Left Maui camp. Maneuvered both days on boats.

p CHARLES H. ORLOSKI: I kept a small book and transposed my notes into a diary. Here's my 11 MAY ENTRY: AM to board APA 166 and transfer to LST; 13 MAY: Maneuvers about to start. First group with amphibian tanks boarded LSTs. Equipment carried: rifles, carbines, belts, canteens, pack, 2 clips, 125 rounds of ammo, 2 sets dungarees, 4 pr socks, 1 pr underwear, helmet, 2 pr shoes, 1 45 cal automatic with 80 rounds ammo, horseshoe roll w 1 blanket & mosquito net, head net, gas mask, knife, mess gear, poncho, extra shoe laces, camouflage head gear, toilet articles. 17 MAY: Left Maui camp. Maneuvered both days on boats.

Note LVT(A)4 on left, LVT(A)1 on right, p23

Note LVT(A)4 on left, LVT(A)1 on right, p23

G. BARRINGER: We told Lt. Pease to check for gas with engine running but he ordered the driver to cut it off anyway. Big mistake. It wouldn't restart nor would our Little Joe Battery recharger. We floated off with our CP man standing up sending semaphore signals. An LST threw us a tow line but we sank anyway.

JOHN ELOFF - Restarting those radial engines was tricky; turn them over 3 times then hit the gas. Never turn them off in battle. That we learned quick.

MARSHALL A HARRIS: Never turn off a hot radial aircraft engine in battle. Starting it hot was far more complex and fussy than a cold engine. Hot radials needed just the right fuel mix at ignition and hot metal plays havoc with cylinder vapor locks, piston and push rods, and magnetos. Radials were also far less forgiving to operate, had limited acceleration and de-accelerating ranges. Burning high octane aviation fuel they turned a amtank into a fire bomb quick.

ROBERT E. WOLLIN: We landed in front of the highest Officers in Hawaii. Admiral Nimitz asked permission for his Admirals to come aboard and inspect. They'd never seen an LVT(A)4 before. One sat in the radio operator's seat next to me. Nervous, I gunned the engine into a large wave, soaking us all, including the Admiral who came up sputtering. You're a private again, I figured. But looking at me he laughed. I should be smarter and realize I'm not a kid anymore and stay ashore where I belong, he said. Getting the portly Admiral out of the hatch and over the side popped off several of his shirt buttons. But we got the job done.

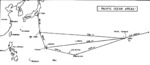

After the 17 May landings in Maalsea Bay the Battalion reloaded its tanks and gear and sailed for battle. Two APAs and 10 LSTs left Maui on 19 May then stopped at Pearl Harbor . 9 of the LSTs left Pearl on 25 May, the last left on the 26th, the two APAs sailed 30 May. Another 9 LSTs sailed directly from Maui for 3,200 miles to Eniwetok. The entire flotilla totalling two APAs and nineteen LSTs assembled at Eniwetok before they all sailed on 10 June for Saipan.

After the 17 May landings in Maalsea Bay the Battalion reloaded its tanks and gear and sailed for battle. Two APAs and 10 LSTs left Maui on 19 May then stopped at Pearl Harbor . 9 of the LSTs left Pearl on 25 May, the last left on the 26th, the two APAs sailed 30 May. Another 9 LSTs sailed directly from Maui for 3,200 miles to Eniwetok. The entire flotilla totalling two APAs and nineteen LSTs assembled at Eniwetok before they all sailed on 10 June for Saipan.

MARSHALL E. HARRIS: Our morale was extremely high. Many years later we'd talk about how our unit's espirit de corps carried us along. It had to do with mutual respect, we all felt it coming up and down the line. Every man got his share and held a respected place whatever his job. So we looked after one another, and held together, for a lifetime really.

REED M. FAWELL - BATTALION: By then we had a Battalion of the finest Marines any unit could have assembled. We were a proud organization and we believed we were ready to fight.

Note: Before he left for battle Col. Fawell reported to General Holland Smith on Battalion's readiness. 68 LTV(A)4s had arrived on 4 May as shells missing all periscopes, telescopes, 30 and 50 Cal machine guns, direct and indirect fire control equipment, blast shields for vision domes, bow guns, dual radio receivers and transmitters, communication accessories, and technical manuals. No missing equipment had been delivered since, save for 40 telescopes and 60 panoramic sights that arrived 12 May. This was after all advanced training (whatever gunnery, tactics, and formation driving its Battalion CO could get across from 5 May to May 10) had ended as Battalion had packed up for maneuvers and sailed for combat. Col. Fawell also reported to the General design flaws built into the LTV(A)4s that would limit combat effectiveness. The amtank's 75 mm howitzer lacked the gyro-stabilizer built into lank tanks allowing the latter to fire with accuracy when on the move. The amtank when sea-borne or moving on land would fire wild. Grossly under-powered, it also had limited mobility. It weighed 20 tons+ when combat loaded but its power plant and power train had been built to move 11 tons. Sea-borne assault troop carrying LVTs would overrun the amtank, masking the amtanks fire. With its engine off the amtank's bilge pumps failed, sinking the amtank in minutes. Faulty waterproofing often shorted out communications and intercom and rendered periscopes useless in a mobile direct fire weapon whose effectiveness was heavily dependent on its mobility, situational awareness and communications. Col. Fawell proposed numerous fixes. He remained confident that his men led by ex-tank and artillery officers and NCOs trained for aggressiveness could produce in any situation as tanks. See Amphibious Tank section 28 May ltr. from Fleet Marine Force Pacific to HQ Marine Corps, Washington DC.

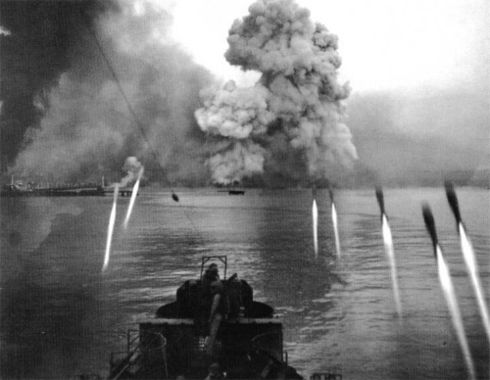

Starting on 19 June a naval armada comprising 800 ships gathered at the Hawaiian islands would begin to sail for Saipan. Fast carrier and battleship strike forces would first engage Saipan on 11 June. Next heavy gunfire ships (old battleships, cruisers, destroyers) would concentrate fire on fixed landing beach defenses, degrading them, before the gunfire ships moved closer inshore and covered the amphibious landings of General Holland Smith's V Amphibious Corps shock troops carried ashore on 15 June in hundreds of smaller landing craft. A vast and varied seaborne logistics train accompanied this warfleet and 71,000 amphibious troops - colliers, oilers, transports, and myriad of speciality ships to support the landing and conquest of Saipan. General Holland Smith's V Amphibious Corps and its logistics train would sail 2250 miles then stage through Eniwetok Atol in the Marshall islands before sailing 950 miles to Saipan.

BATTALION Sails 3,200 MILES to SAIPAN via ENIWETOK from 19 MAY to 14 JUNE 1944:

GLENVILLE BARRINGER : After our tank sank in Maalsea Bay, we got a new one without ammo racks. Sailing to Saipan we built new racks from wood, a hot job in a tank down in LST's hold. MARSHALL E. HARRIS: My quarters aboard LST 450 was a newly liberated Navy mattress spread across my amtank's front deck parked below against the LST's bow doors shut like a clam to keep the seawater out. We'd fall asleep listening to the rhythmic beat of giant doors surging through sea swells. For 3 weeks our 5 amtank platoon shared the LST with the Infantry Company & LVTS we'd lead into battle. I went from June 2 to June 4 in one second crossing the International Date Line at mid-night.

JERRY D. BROOKS: Our convoy comprised lines of ships from horizon to horizon going from Maui to Saipan in early June of 1944. Our LST, a sea-going barge whose topside was jammed with trucks, jeeps, and various odds and ends that came in handy in questionable real estate transactions, chugged along as fast as the slowest ships could go. The smallest torpedo or mine could sink us in minutes. So little destroyers raced up and down the lines of the convoy blinking their signal lights wildly, impressing us with their importance in keeping Japanese subs at bay. Many of us stayed topside at night and slept beneath tarps slung between vehicles anchored to the deck.

p25

p25

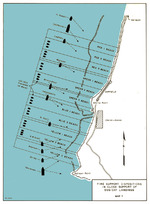

ROBERT E. WOLLIN - COMPANY D: My platoon left Maui on LSD 485. Everything aboard was jammed to the scuppers. Each LSTs carried an Infantry Company as well as its supporting weapons and units; its machine guns and mortars, a platoon of 8 tracked amphibious vehicles (LVTs) to carry the Infantry Company ashore, and our platoon of amtanks to lead its assault ashore. Our amtanks, being the first assault wave, were the last aboard the LST, and parked up tight against its huge bow doors. In transit to battle, we slept on the LST's main deck, under life boats, behind engines or wheelhouses, or under or in medium sized ships called LSPs (landing ship personnel), gunboats (LCTs) or LSMs that transported land tanks ashore. These smaller ships sat on blocks. Huge chains lashed them to the LST's deck. In battle, after our Amtanks and LVTs had left for shore, the ship's captain flooded one side of the LST and its smaller ships slid off the deck into the sea. So each Assault Company was wrapped up in one neat package that was loaded aboard the LSD that then transited it to battle, prepacked and ready to launch its package of war machines and men into their seaborne assault across the sea, over reefs, through lagoons, then up onto the beach before its thrust inland, busting through enemy defenses. That was our mission. We shipped out and went ashore with a very gun ho bunch - G Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines, 2nd Marine Division.

WINTON W. CARTER - COMPANY B: On 21 May our LST docked at Pearl Harbor and unloaded our amtanks so other gear could be loaded in behind them. We'd parked some a 100 yards away when our Gunner began cleaning his howitzer, sliding a shell in an out of its chamber. Watching him, I said: If you let that thing go off, you've had it. Then - BOOM! My first thought was he did it, fired it. Then a guy shouted: Look at that! Smoke and flames shot out of our LST. LSTs moored alongside lit afire then exploded. Sailors leapt overboard. Some got ground up in churning propellers. Shrapnel whizzed by us, ammo, fuel, acetylene tanks, you name it, exploded exploded, cooking off.